CONTINUED FROM MODULE 2 PART 2

BEHIND THE CAMERA

Figure 2-05-001

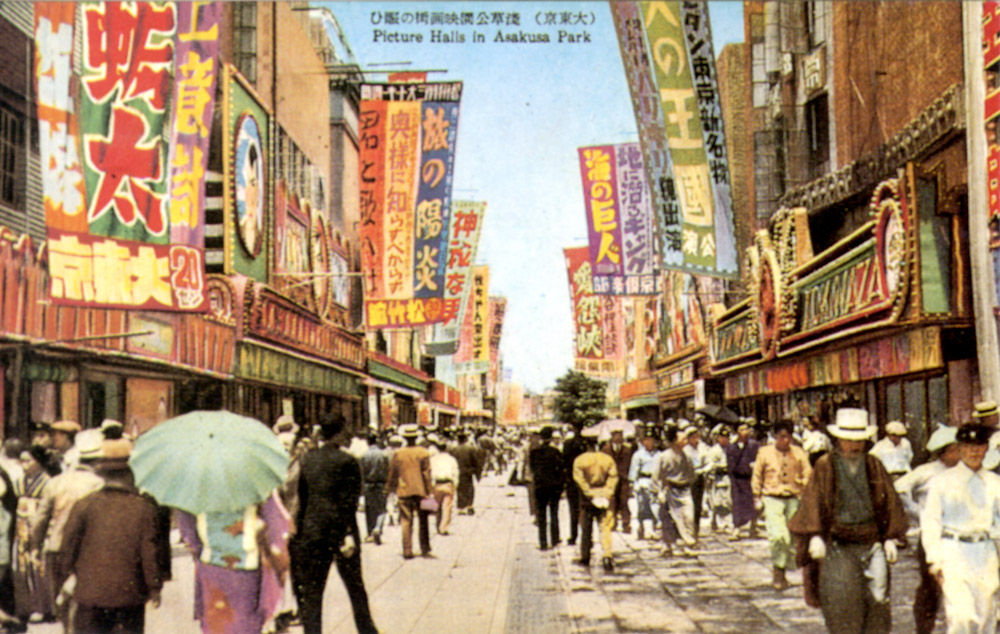

This colorful postcard (Fig. 2-05-001) dates from around 1937, the year that four Japanese companies merged to form Tōhō studios. Among them was Photo Chemical Laboratory (PCL), established in 1932, which is the date Tōhō officially gives as the year of its corporate founding. In cultural and political terms, the decade that saw these events unfold—the Thirties—witnessed momentous transformations in Japan as well as elsewhere around the world.

In the realm of Japanese cinema, one of the most significant developments of the Thirties was a transition from silent to talking pictures. Among its other consequences, the introduction of sound technology ultimately throttled the livelihood of Japan’s benshi, live narrators whom theaters had formerly hired to voice the characters’ lines and to comment on the screen action, and who often attracted a following in their own right. As was the case in Hollywood, not everyone in the film industry survived the shift to talkies. Others, however, did. One cinema giant who successfully bridged the pre- and post-talkie eras was director MIZOGUCHI Kenji (1898–1956), whose 1937 sound feature Aienkyō (Straits of love and hate) was playing at one of the Tokyo theaters on the right side of the postcard when the photo was taken.

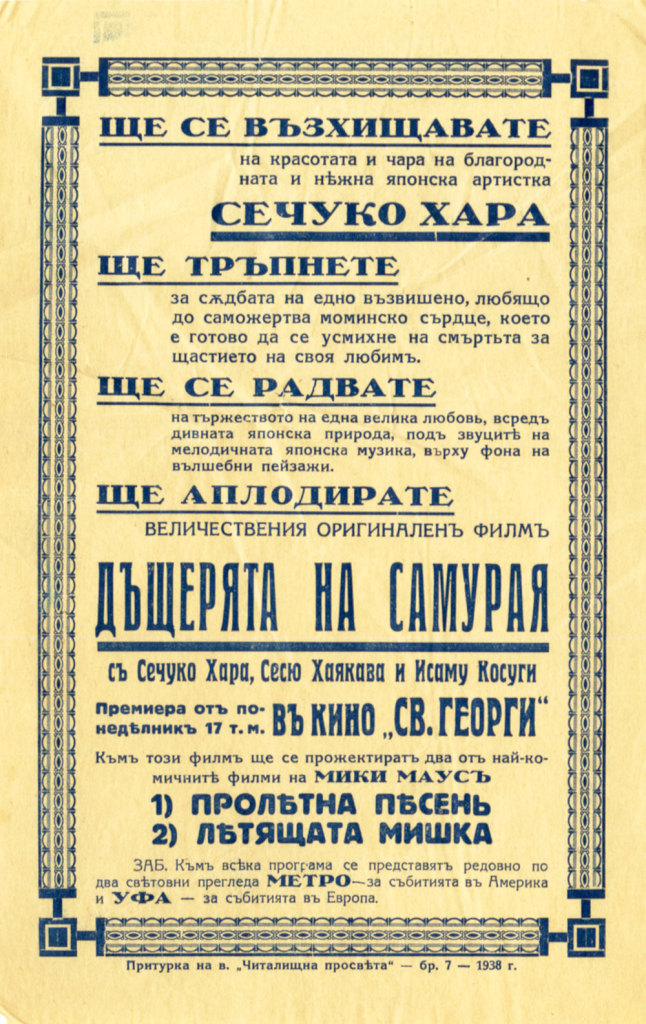

Another significant cinematic development of 1937 was the first-ever coproduction between Japan and Nazi Germany. The two nations had concluded a political alliance, known as the Anti-Comintern Pact, the previous year. (Italy joined that pact in 1937.) Codirected by Arnold Fanck (1889–1974) and ITAMI Mansaku (1900–1946), The Daughter of the Samurai brought together some of the leading figures of contemporary German and Japanese cinema. Its storyline glorified the virtues of cultural tradition and of racial purity and received a stamp of approval from both Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels. (Goebbels noted in his diary, however, that the movie was unbearably long.) If the coproduction’s underlying goal was to demonstrate to German and Japanese audiences that their two peoples cherished similar ideals, then the directorial tensions that arose between Fanck and Itami threatened to undercut that very message. As a result, two different versions of the picture were released: one of them, Die Tochter des Samurai, in Germany (Fig. 2-05-002) and other parts of Europe, and the other, Atarashiki tsuchi, in Japan and its fast-growing empire.

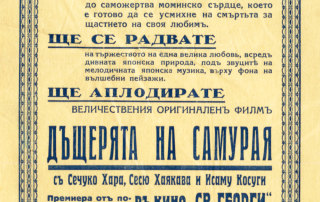

Even with its blatantly fascist political agenda, the German-Japanese propaganda film broadened the geographic horizons of Western moviegoers far beyond the borders of Germany. In January (or else October) 1938, for example, The Daughter of the Samurai—the German version, translated locally as Dshcheryata na samuraya—headed the marquee at the St. George cinema in an unidentified city (possibly Ruse) in the then-kingdom of Bulgaria. Communicating the picture’s allure through florid language rather than publicity images, a printed broadsheet (Fig. 2-05-003) circulated by the St. George’s management invited audiences to “rejoice in the celebration of a great love amidst the glories of Japanese nature, to the melodious accompaniment of Japanese music, against the backdrop of a magical landscape.” Singling out the performance of the “noble and gentle” Japanese actress HARA Setsuko (1920–2015) in the title role, the St. George promised Bulgarian viewers they would “tremble at the fate of her sublime, self-sacrificing, maidenly heart, ready to smile at death for the happiness of her lover.” Hitler was no match for Hollywood, however, even at the St. George. Filling the other half of the bill with the German-Japanese drama was a pair of Disney cartoons starring a ten-year-old, but already world-famous, Mickey Mouse.

The film that German, Bulgarian, and other European audiences of the Thirties knew as The Daughter of the Samurai, moviegoers in Japan watched under the title Atarashiki tsuchi, with a considerably different content. The Japanese name literally means “new soil,” but in the context of the Thirties, the phrase tended to refer more specifically to northeastern China, a region that the imperial Japanese military had taken control of in 1931. Japan’s invasion laid the ground for the puppet state of Manchukuo, which was officially born in 1932 but which few nations besides Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ever formally recognized. Japan’s military adventures on the Asian mainland met with widespread international condemnation, to which the Tokyo government responded by withdrawing from the League of Nations in 1933.

Figure 2-05-004

In July 1937, Japanese military involvement in China escalated into all-out war. And eventually, after the Pearl Harbor attack of December 1941, the larger Asia-Pacific region would become one of the two main theaters of operation in the all-encompassing conflict that today we know as World War Two. Yet even in the midst of momentous historical upheaval, people find ways to go about their everyday lives. In at least one sense, the scene on the above postcard differed little from what could be found in the same neighborhood whether it was the middle of the twentieth century or the middle of the nineteenth: a robust market for popular entertainment. A bevy of kabuki theaters began operating in the working-class district of Asakusa in 1841 (as reflected in Hiroshige’s woodblock print [Fig. 2-05-004] of the same neighborhood in the 1850s), followed by the nation’s first permanent cinema in 1903. Whether in peacetime or war, commercial spectacle continued to draw a paying audience.

If one of the origins of Gojira lies in the volatile atomic politics of the early Cold War era, another must be sought in the broader history of the film medium. Cinema’s beginnings in Japan, as in Europe, the Americas, and elsewhere, date to the last years of the nineteenth century. The Japanese film industry was thus already more than a half-century old when Godzilla first lumbered onscreen. What is conventionally called the studio system, which ties actors, writers, directors, and other film workers to a particular movie corporation on an ongoing basis, has survived considerably longer in Japan than in Hollywood. The particular cinematic enterprise that made Gojira, namely Toho Co., Ltd. (referred to on this website as Tōhō), was founded in Tokyo in 1932, reorganized and renamed in 1937, and remains one of the industry’s major players. During the studio’s early years [VISUAL SIDEBAR 5: Setting the Stage], Tōhō enjoyed renown for, among other things, its comedy features and period pieces. It boasted among its stable of actors the legendary ENOMOTO Ken’ichi (1904–1970), or “Enoken,” sometimes known as Japan’s Charlie Chaplin. Although the studio’s export business is largely a postwar story, Tōhō’s prominence in the Japanese film industry spans the prewar, wartime, and postwar years.

Visual effects stand the best chance of convincing when you can’t see the wires that hold the illusion together. But even if the puppet master is invisible, it’s he or she who makes the show possible in the first place. In the case of Gojira, as well as a large number of its sequels, the man who pulled the strings, both literally and figuratively, was special-effects director TSUBURAYA Eiji.

Visual effects stand the best chance of convincing when you can’t see the wires that hold the illusion together. But even if the puppet master is invisible, it’s he or she who makes the show possible in the first place. In the case of Gojira, as well as a large number of its sequels, the man who pulled the strings, both literally and figuratively, was special-effects director TSUBURAYA Eiji.

Even before the making of Gojira, Tsuburaya’s technical skills and artistry had earned him a lasting place in Japanese film history. When he was only twenty-five, working with the legendary director KINUGASA Teinosuke (1896–1982), Tsuburaya’s assistance with the camera left a subtle mark, for example, on the 1926 surrealist classic Kurutta ippēji (A page of madness). That experimental film was based on a scenario by KAWABATA Yasunari (1899–1972), who would receive a Nobel Prize for literature several decades later.

An important turning point in Tsuburaya’s career came with Hawai Marē oki kaisen (The war at sea from Hawaii to the Malay Coast), a Tōhō production of 1942. Directed by YAMAMOTO Kajirō (1902–1974), Hawai Marē oki kaisen was released a year after the attack on Pearl Harbor and thrilled Japanese audiences of the time by recreating the event on a hand-built miniature set that Tsuburaya and his team had painstakingly designed to scale. These souvenir photos (“bromides”; Fig. 2-06-001, Fig. 2-06-002) from the film are hardly recognizable as trick photography and even bear the inscription “Passed by Naval Censors.” Ironically, Tsuburaya had modeled his Pearl Harbor set on images he found in American photojournalism, because the Imperial Navy, while officially sponsoring the film’s production, kept its military intelligence closely guarded. Tsuburaya’s future collaborator HONDA Ishirō viewed Hawai Marē oki kaisen while serving as an Imperial Army soldier on the China front, and it made a strong impression. Other Tōhō staff who worked with Tsuburaya on the set of Hawai Marē oki kaisen included WATANABE Akira (1908–1999) and TOSHIMITSU Teizō (1909–1982), who would later join hands to design Godzilla’s trademark rubber suit.

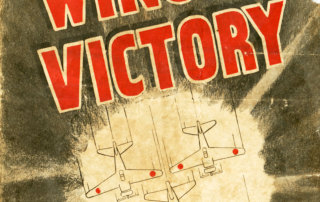

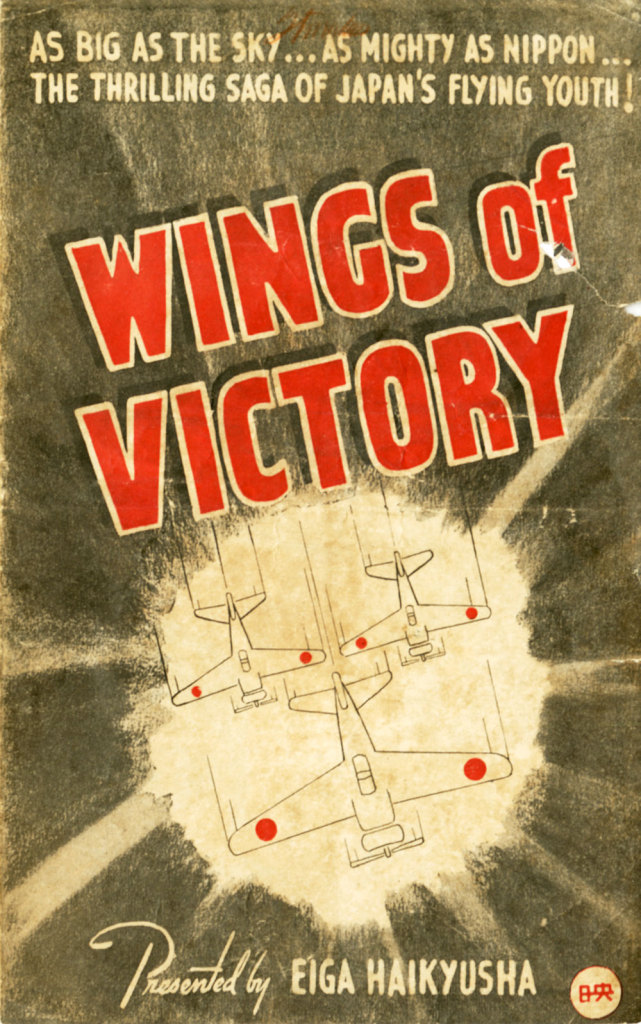

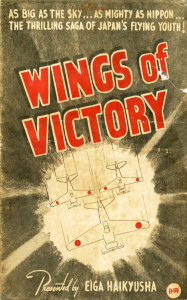

As a rule, Japanese propaganda films of the war period, such as Hawai Marē oki kaisen, didn’t play in English-speaking countries, since the latter generally belonged to the Alliance and not the Axis. Nevertheless, Japanese wartime films were shown in conquered regions like the Philippines, where English was widely spoken after more than four decades of American colonial rule. Japanese forces occupied the Philippines shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, occasioning MacArthur’s famous “I shall return” remark. An English-language leaflet (Fig. 2-06-003, Fig. 2-06-004) from the occupied Philippines advertises Tōhō’s 1942 production Tsubasa no gaika (international title: Wings of Victory), for which TSUBURAYA Eiji designed the special effects. In addition, one of the screenwriters for the film was a young KUROSAWA Akira. Echoing the soaring rhetoric of the wartime Japanese government, the pamphlet refers to the fighter plane that the film’s heroes design and fly as a “liberator of Southern Skies from Anglo-American imperialism.”

Kurosawa was a relatively unknown figure even in Japan during the early Forties, so it’s not surprising that his screenwriting role receives no mention in the English-language herald. A more familiar name for moviegoers in Japan’s wartime empire was that of ŌKAWA Heihachirō (1905–1971), which appears third in the pamphlet’s list of stars, albeit in a surname-first “Western” order so as to accommodate an overseas audience. Ōkawa, who was born and raised in Japan, had briefly pursued a career in Hollywood during the early Thirties, working, among other things, as an aerial stuntman for Howard Hawks. Upon his return to Japan he continued to use the English nickname Henry alongside his given name of Heihachirō. The Wings of Victory flyer downplays these more cosmopolitan aspects of Ōkawa’s star identity, in keeping with its broader indictment of “Anglo-American” influences. That’s presumably Ōkawa in a crisp Imperial Navy uniform on the interior of the flyer.

Skill in English came in handy in the occupied Philippines, where Japanese military authorities posted Ōkawa in 1943 to help film the propaganda epic Ano hata o ute: Korehidōru no saigo (Fire on that flag! The last days of Corregidor; 1944)—in theory a Japanese-Filipino “coproduction”—and where, in 1945, he ended up as an interpreter for the surrendering Japanese general YAMASHITA Tomoyuki, the so-called Tiger of Malaya. One wonders how much Ōkawa’s Allied interlocutors knew of the part he had played in Ano hata o ute, whose filming required hundreds of traumatized American POWs to recreate the 1942 U.S. surrender of Bataan and Corregidor, thus arguably constituting a war crime in itself.

In Japan, as nearly everywhere, movie production during World War Two gravitated toward patriotic themes. Some of the most popular films of the war era were military dramas and other propaganda vehicles, which required the construction—and destruction—of elaborate miniature sets. Tōhō’s special-effects wizard TSUBURUYA Eiji (1901–1970) [VISUAL SIDEBAR 6: The Puppet Master] honed the skills that made Godzilla’s rampages so visually impressive by choreographing battle sequences for precisely such wartime features. In this way, as in others, the kaijū eiga genre built upon the existing infrastructure and achievements of Japan’s film industry, which had only recently weathered a global conflict. Tokusatsu, the Japanese word for special effects, and tokusatsu eiga (special-effects film) are terms frequently used to refer to movies that rely heavily on miniature models and other techniques of illusion, whether they depict historical events such as naval battles or out-and-out fantasy.

When it comes to Japanese exports, the Honda name has given the world more than just great cars and motorcycles. Although he bears no familial relation to the automaking giant, Tōhō-based director HONDA Ishirō managed over the course of his career to rack up just as much mileage as his corporate namesake, not on the world’s roadways but on its movie and TV screens. In 1956, when Honda’s Gojira hit the U.S. theater circuit as King of the Monsters, there were few members of his Stateside audience who had ever driven a Japanese vehicle, much less one from Honda Motor Company, which hadn’t yet entered the U.S. market. Yet well over three million Americans flocked to their local theaters to watch King of the Monsters, and many more would subsequently watch its sequels, not just in North America but on all the world’s populated continents. It’s ironic that Japan’s “other” Honda enjoys scant name recognition among overseas consumers, despite a fairly widespread familiarity with its bearer’s handiwork. Whereas far more people probably know the name of fellow Japanese director KUROSAWA Akira than have actually watched a Kurosawa film from start to finish, the opposite holds true for Honda, his studio colleague.

When it comes to Japanese exports, the Honda name has given the world more than just great cars and motorcycles. Although he bears no familial relation to the automaking giant, Tōhō-based director HONDA Ishirō managed over the course of his career to rack up just as much mileage as his corporate namesake, not on the world’s roadways but on its movie and TV screens. In 1956, when Honda’s Gojira hit the U.S. theater circuit as King of the Monsters, there were few members of his Stateside audience who had ever driven a Japanese vehicle, much less one from Honda Motor Company, which hadn’t yet entered the U.S. market. Yet well over three million Americans flocked to their local theaters to watch King of the Monsters, and many more would subsequently watch its sequels, not just in North America but on all the world’s populated continents. It’s ironic that Japan’s “other” Honda enjoys scant name recognition among overseas consumers, despite a fairly widespread familiarity with its bearer’s handiwork. Whereas far more people probably know the name of fellow Japanese director KUROSAWA Akira than have actually watched a Kurosawa film from start to finish, the opposite holds true for Honda, his studio colleague.

Figure 2-07-001

As it happens, the two Tōhō directors enjoyed a long association both personally and professionally. In 1949, for example, Honda, who had yet to direct his own film, assisted Kurosawa in directing Stray Dog (J. title: Norainu), one of Kurosawa’s early masterpieces. Honda even played a small onscreen role as a fleeing villain. This printing block (Fig. 2-07-001) for Stray Dog originates from the Chicago area and is of unknown date, but was likely made in the Fifties or Sixties. Newspapers, cinemas, and film distributors in the United States used blocks like this one to produce various types of programs and advertisements.

Following his retirement, Honda would again collaborate with Kurosawa on several of the latter’s mature classics. Kurosawa’s samurai epics Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985) both received Honda’s directorial assistance, as did Kurosawa’s very last picture, Mādadayo (1993), a historical biography. But it was in 1990’s Dreams (J. title: Yume) that Honda left his most conspicuous mark on the Kurosawa film legacy. Billed overseas as Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, the movie consists of eight loosely tied vignettes, two of which Honda took primary responsibility for directing, working on the basis of Kurosawa’s detailed storyboards. The themes of both struck close to Honda’s heart: the nightmare of World War Two (“The Tunnel”; Fig. 2-07-002) and the perils of nuclear technology (“Mount Fuji in Red”; Fig. 2-07-003). Japan’s nuclear experience takes center stage also in a third segment of Dreams that Honda partially directed (“The Weeping Demon”; see Fig. 2-07-004, with its giant mutated dandelion), as it would again in Kurosawa’s next-to-last film, Rhapsody in August (1991; Fig. 2-07-005), on which Honda served as a creative consultant.

Since Honda and Kurosawa both worked for the same studio, they regularly drew on the same pool of actors. One notable exception is Kurosawa mainstay MIFUNE Toshirō (1920–1997), whose name appears on the above printing block for Stray Dog. Despite—or perhaps because of—his international star power, Mifune would never perform in a Godzilla movie. Indeed, Mifune worked under Honda’s direction only on a handful of occasions, just one of them, 1953’s Operation Kamikaze, involving special effects.

Figure 2-07-006

By contrast, Mifune’s Stray Dog costar SHIMURA Takashi (1905–1982; the gentleman at right in Fig. 2-07-006) shared the screen with quite a few kaijū over the course of his career. The accomplished actor plays a central role in 1954’s Gojira as Dr. Yamane, the kindly paleontologist who first identifies the monster’s origins as an irradiated dinosaur. In later years, Shimura would likewise appear as a good-guy authority figure in such tokusatsu classics as The Mysterians, Mothra, Gorath, and Frankenstein Conquers the World, all directed by Honda, along with two more Godzilla movies. Even NAKAJIMA Haruo (born 1929), the first stuntman to wear the Godzilla suit, earlier performed on the set of Kurosawa’s Stray Dog: in a scene that was eventually cut, he threw his weight around in a barroom brawl.

Figure 2-07-007

A word or two about Japanese names may be helpful here. The “Inoshiro Honda” of this Italian poster (Fig. 2-07-007) is the same person as the “Ishiro Honda” credited on many other publicity materials from around the world. Properly speaking, “HONDA Ishirō” is how the director would have identified himself, in the standard Japanese order—family name first, given name second. To avoid confusion, I capitalize family names on this website when citing them in non-Western order. For the record, Honda’s given name should be pronounced Ishirō and not, as the Italian poster suggests, Inoshirō, even though the latter is a fairly common misreading even in Japan. This particular poster was made to advertise Operation Kamikaze (J. title: Taiheiyō no washi), a Honda-directed feature film from 1953, set during World War Two.

During the Thirties and Forties, Honda had himself taken part in that catastrophic conflict. Twice drafted into Japan’s imperial army, Honda served as an infantryman on the China front, where he was captured in 1945, shortly before Japan’s defeat. When he wasn’t soldiering, Honda also served the imperial cause as an assistant director on two battle pictures from Tōhō, whose predecessor studio, PCP, Honda had begun working for in 1933. Both these war dramas—Katō hayabusa sentōtai (Katō’s falcon squadron; 1944) and Raigekitai shutsudō (Torpedo squadrons move out; 1944)—were directed by YAMAMOTO Kajirō, who was Honda’s and Kurosawa’s studio mentor. Although American authorities banned overt military themes from cinema during their postwar occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1952, war movies made a quick recovery upon the censors’ departure. A number of studio officials whom American authorities had purged during the occupation also returned to the industry after 1952, among them Gojira‘s executive producer, MORI Iwao (1899–1979).

Honda, on the other hand, would over the course of the Fifties distance himself from war movies—or at least war movies of the conventional kind. After making two World War Two dramas (Operation Kamikaze and Farewell Rabaul [J. title: Saraba Rabaūru]) in quick succession, the director would take on no more such projects after the 1954 launch of the Godzilla series. In a broader sense, however, made-in-Japan monster movies inherit much of their dynamism and penchant for destructive spectacle from their historical and technological linkages with the battle-picture genre. Military themes, and personnel, in fact appear quite frequently in kaijū eiga, the genre that Honda helped to pioneer. And in a postwar Japan whose American-drafted constitution didn’t allow the nation to keep a full-fledged or even openly recognized army, the sight of Japanese soldiers fighting monsters was arguably no less “realistic” a subject of visual entertainment than were wars of the past with human enemies.

Figure 2-07-008

Not long after his studio colleague Honda made Gojira, KUROSAWA Akira, too, responded to the Lucky Dragon incident through the medium of film. Although ticket sales paled in comparison to Honda’s blockbuster of the previous year, 1955’s I Live in Fear (J. title: Ikimono no kiroku), marks Kurosawa’s first foray into antinuclear cinema. Even without monsters, the movie makes a haunting impression. It tells the story of an elderly Japanese man, played by—who else?—MIFUNE Toshirō, whose fears of imminent nuclear annihilation fuel a gradual descent into madness. I Live in Fear remains one of the less appreciated works of Kurosawa’s middle period. This U.S. publicity still (Fig. 2-07-008), which most likely dates from the late Sixties or Seventies, gives the name of an art-house distributor. Such was the route by which most of Kurosawa’s work reached the United States, in contrast to Honda’s greater mainstream visibility.

The career of Gojira‘s co-writer and director HONDA Ishirō [VISUAL SIDEBAR 7: Japan’s Other Honda], like that of his special-effects collaborator Tsuburaya, similarly got its start long before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Although he’s best known today for his work on the Godzilla series, Honda built up an extensive and diverse list of credits between the Thirties and his death in the Nineties. In addition to directing his own films, he served on several occasions as assistant director to his studio coworker and close friend, KUROSAWA Akira (1910–1998). It’s a sign of Honda’s lesser renown than Kurosawa’s that even Japanese people are known to mispronounce his given name as “Inoshirō,” a more common reading for the same characters. How many people today remember that in 1955, Honda’s Gojira and Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai) both received nominations for Best Film of the previous year in the contest for Japan’s equivalent of the Academy Awards? It was Kurosawa who walked away with the prize, and who would consistently walk a step ahead of his colleague in terms of critical reputation. Ironically, however, as a consequence of the studio system, the two men’s films made use of many of the same actors and crew.

The name of another one of Godzilla’s creators, TANAKA Tomoyuki, has already been mentioned. As producer and initial conceptualizer of the film that would eventually become Gojira, Tanaka played just as important a role behind the scenes as the picture’s director, Honda, or special-effects mastermind Tsuburaya. During the Fifties, Tanaka was one of two Tōhō staff producers who together helped shape the studio’s output. The projects he supervised tended to be action-oriented, appealing above all—although by no means exclusively—to male audiences. Today, more people remember the names of Tsuburaya and Honda than that of Tanaka, but among the trio, Tanaka was in fact the most consistently involved in the Godzilla series during the era on which this website focuses, which is to say, the Fifties through the Seventies. Whereas in six of the period’s Godzilla movies, Honda turned over the director’s chair to colleagues such as ODA Motoyoshi (1910–1973) and FUKUDA Jun (1923–2000), and although Tsuburaya passed away in 1970, Tanaka oversaw the production of every Godzilla feature, along with many other tokusatsu films at Tōhō, until 1995. The publicity strategies surrounding the kaijū eiga thus owe a great deal to Tanaka’s business know-how.