REMEMBERING UNCOOL JAPAN: A Personal History

Gregory M. Pflugfelder

©2015

Why Godzilla? Naturally, I face this question quite a bit. Before attempting an answer, I want to set the record straight about a few things that might otherwise be assumed about me or about anyone who focuses his attention on such an unconventional—some might say unscholarly—topic.

- I’ve never played with a Godzilla toy. Truth be told, as a child I secretly coveted a Barbie doll or an Easy-Bake Oven. But that’s another story.

- Never once have I attended a Godzilla convention. In fact, people in costumes embarrass me inordinately.

- There are some movies in the Godzilla series whose plots seem so lame and production values so dismal that I cannot bear to view them in one sitting.

Having said that, I won’t deny that, late in life as far as these things go, Godzilla has cast an odd spell over me. My fascination is pleasurable, but it also has an intellectual basis. It connects with three of my broader interests as a scholar and a teacher, and it brings them together in a unique way. As a historical figure of consequence, as a global icon, and as a multimedia visual phenomenon, Godzilla cut a deep and lasting swath across the cultural landscape of the late twentieth century, and holds his tail high even in the new millennium. As a way of explaining my goals in developing this website, I’ll expand below on each of these three facets of Godzilla and of my approach to him as a scholar and an unlikely suitor: the historical, the global, and the visual.

GODZILLA AND HISTORY

For the record, I’m a historian. It’s not a glamorous occupation, but on the other hand it’s rarely boring. Simply put, what historians do is use materials from the past, whether recent or remote, to tell stories that are of interest or relevance to those who live in the present. In this age of megamedia, it’s hardly surprising that a growing number of scholars have turned their attention to studying the history of mass entertainment, which exerts a pervasive influence in contemporary society. Academic writings on pop culture range in quality from the ridiculous to the sublime, but they prove at least that the stuff of history doesn’t have to be stuffy. This website is my own attempt to join this broader conversation on popular culture, which unites the interests of academics and the general public.

Growing older has a special poignancy for historians. Among our kind, the past is both personal and professional, since inevitably the passage of years causes lived experience and historical reflection to merge. Eventually, every historian becomes not just a student but also a living embodiment of history, a walking textbook in the truest sense. For Baby Boomers like myself, the Nineteen Fifties, Sixties, and Seventies long remained too fresh in memory, seemed too familiar, too spick and span, to deserve the hallowed name of “history.” It’s a sobering experience to realize that most of the undergraduates whom I teach at Columbia University are children of the Clinton and Bush eras, conceived years after I myself entered college. For them, the Vietnam War is the subject of movies and fiction, just as World War Two or the Korean War were for people my own age. To put it another way, the original Godzilla was born to and inhabited a world that has long since passed. In making that past come alive, I therefore have the ambiguous pleasure of reliving my own history. Creating this website has also renewed my sense of kinship with those who share the memory of that now-lost world, and who were similarly shaped by it. We will always be the Godzilla Generation.

Figure 1-01-001

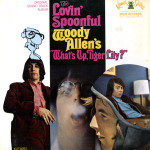

This Spanish poster (Fig. 1-01-001) for What’s Up, Tiger Lily? is a product of the early Eighties, a time of swelling international admiration for Japan’s economic success. Spanish film promoters hoped that Woody Allen’s “most Japanese” comedy would similarly succeed in their own country in 1981, two years after the publication of Harvard sociologist Ezra Vogel’s bestseller Japan as Number One, the Spanish title of which one of the poster’s taglines echoes. I can’t resist noting that, as a senior at Harvard around the same time, I flunked out of Professor Vogel’s class on “Japanese Society.” (It’s a long story.) Vogel’s book, a paean to Japanese business practices, failed to predict the doldrums into which the Japanese corporate economy as a whole would fall during the post-Bubble Nineties, even as Japanese cultural creativity continued to grow in influence around the globe.

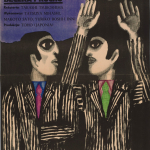

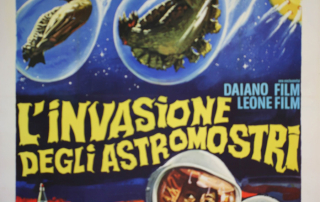

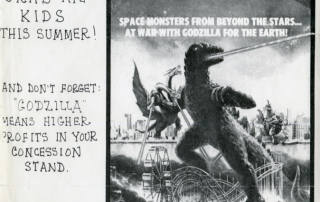

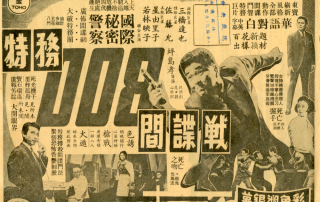

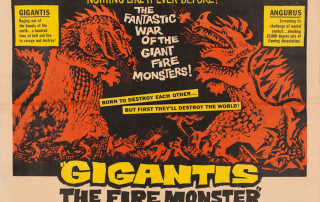

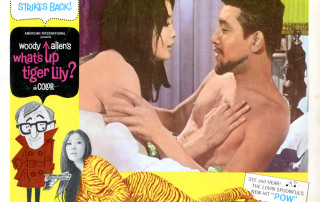

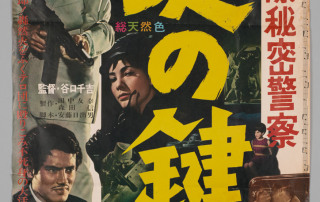

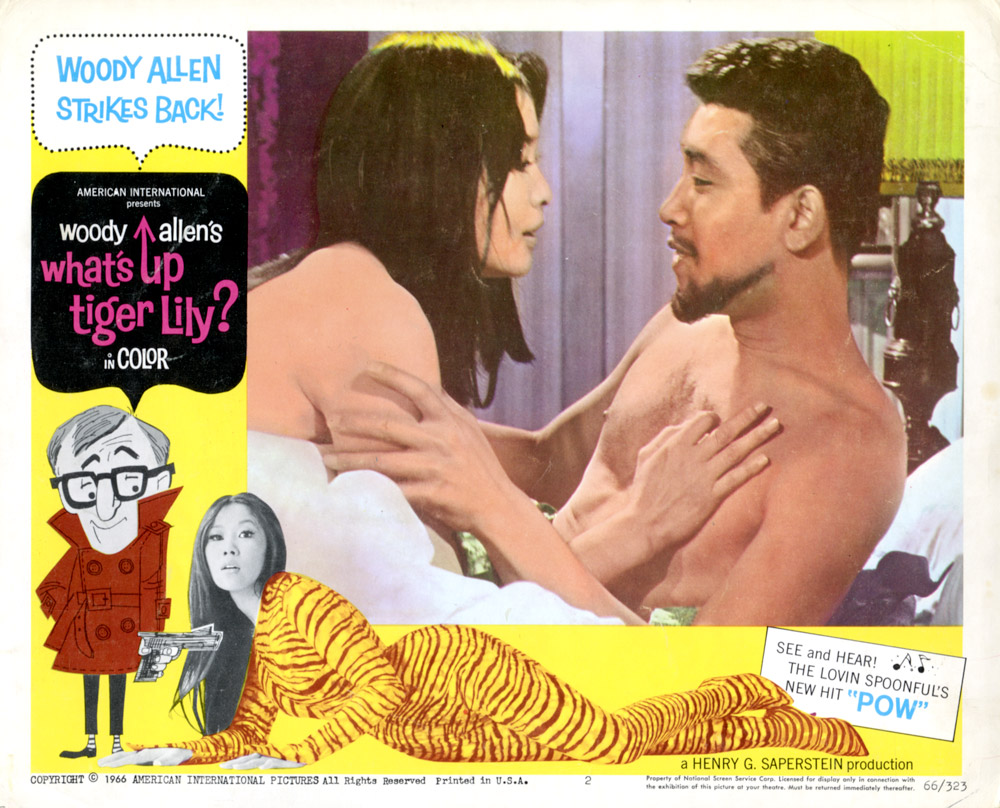

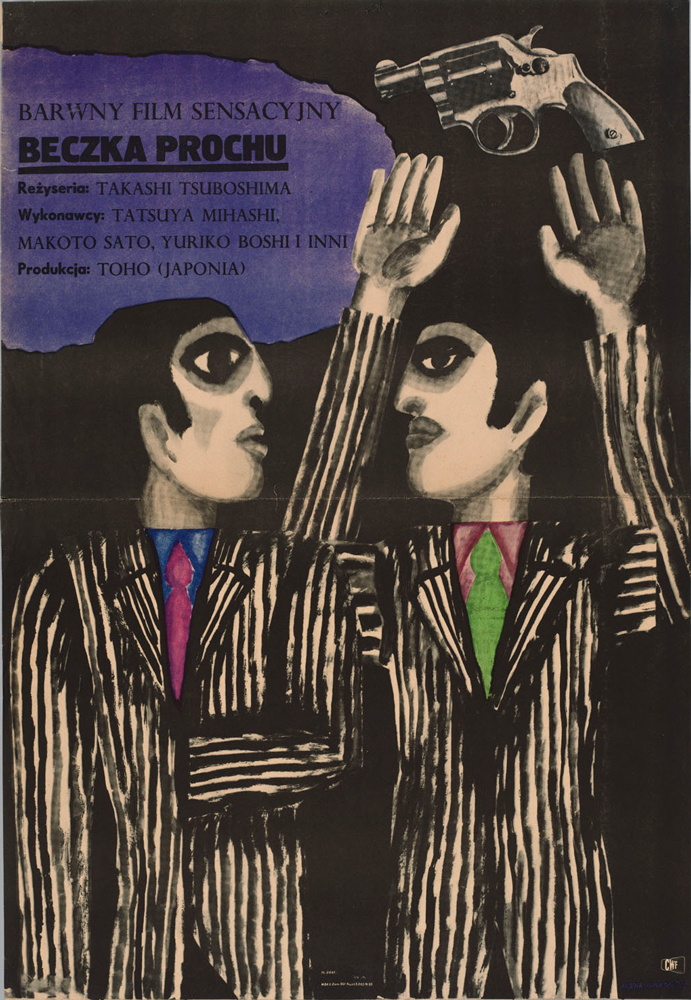

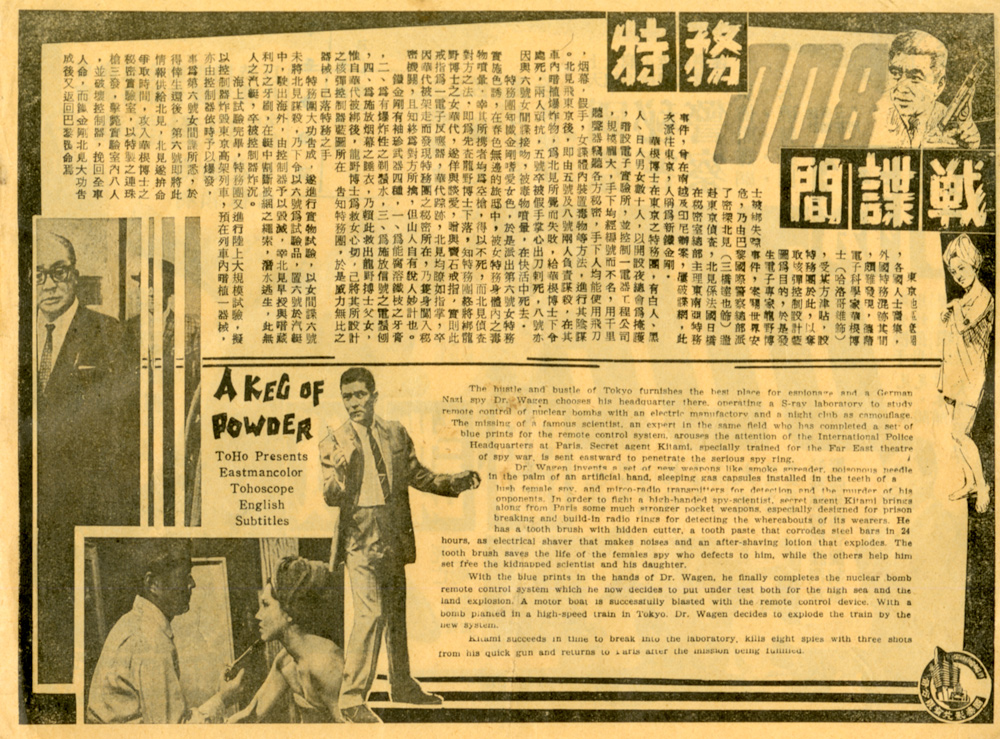

What’s Up, Tiger Lily? is the product of an earlier era, a time when Japan was far less cool. In fact, it’s really two film products: one of them a 1965 spy movie made at Japan’s Tōhō studios, and the other a 1966 Hollywood release that retained the original Japanese footage but overlaid it with a wacky English-language script by comedian-director Woody Allen about the search for a secret egg-salad recipe. The 1965 film is more properly called Key of Keys (J. title: Kagi no kagi; Fig. 1-01-002) and marks the fourth entry in a five-part string of spy romps—the Kokusai himitsu keisatsu (International Secret Police) series—that Tōhō studios launched in 1963 to emulate the Anglo-American James Bond franchise. In some markets—see, for example, this Thai poster (Fig. 1-01-003) and this Singaporean herald (Fig. 1-01-004)—publicists went so far as to assign the series’ Japanese hero the codename “008,” in effect one-upping the British agent’s more familiar “007.” The third entry in the Tōhō series, A Keg of Powder (J. title: Kayaku no taru; 1964), whose plot the Singaporean herald conveniently summarizes (Fig. 1-01-005), contributed a few scenes to What’s Up, Tiger Lily? as well. Although Tiger Lily didn’t play behind the Iron Curtain, viewers in Communist Poland (Fig. 1-01-006) and Yugoslavia (Fig. 1-01-007) would probably have recognized those scenes, since A Keg of Powder was one of a number of carefully vetted West Bloc spy flicks allowed to circulate in Eastern Europe during the genre’s Cold War heyday, among them several from Tōhō studios.

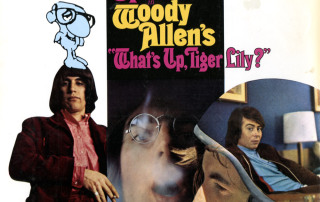

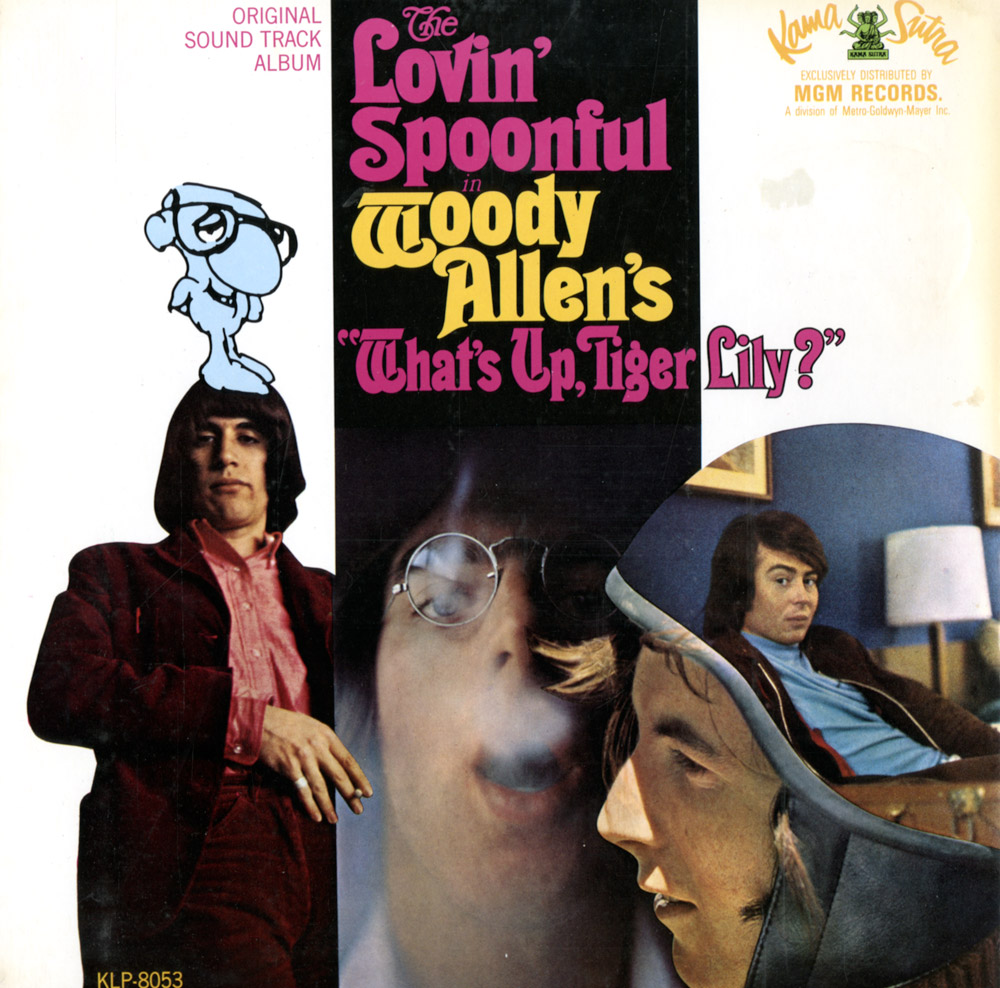

Although What’s Up, Tiger Lily? marked Allen’s debut as a director, what first garnered him attention in Hollywood was his screenwriting and acting turn in the 1965 Franco-American comedy What’s New Pussycat? (Fig. 1-01-008), which also inspired What’s Up, Tiger Lily‘s peculiar title. Tiger Lily‘s hip soundtrack (Fig. 1-01-009), by The Lovin’ Spoonful (Fig. 1-01-010), likewise betrays the influence of What’s New Pussycat?, whose theme song of the same name, performed by Welsh crooner Tom Jones, was already on its way to becoming one of that Sixties icon’s signature hits.

What makes What’s Up, Tiger Lily? a priceless resource for film-historical purposes is Allen’s parodic engagement with the low-budget international movie market as Americans of the Sixties (including myself) knew it. Ironically, that booming business was one that Tiger Lily‘s distributor, American International Pictures—founded in 1954, the year that birthed Godzilla—had played a central role in shaping. It’s not clear to what extent AIP studio heads Sam Arkoff (1918–2001) and James Nicholson (1912–1972), both pioneers of exploitation cinema, recognized or appreciated the irony, or whether anything other than the bottom line was on the mind of Tiger Lily‘s co-producer Hank Saperstein (1918–1998), a Japan-savvy Hollywood promoter who brokered many of the AIP-Tōhō collaborations of the Sixties. The irony is striking, nevertheless. Even as Hollywood outfits like Nicholson and Arkoff’s AIP and Saperstein’s UPA made a lucrative business out of procuring the rights to made-in-Japan films and then reediting and releasing them in dubbed English-language versions full of clumsy translations and inconsistent plotlines, fake accents and ethnic stereotypes, Allen created a new genre of film comedy by deliberately highlighting and exaggerating those familiar conventions for humorous effect. Both having his cake and eating it, Allen poked fun at Uncool Japan’s growing presence on the movie screens of white-bread America while still lining the pockets of his AIP associates.

As the folks at AIP knew well, repackaging foreign-made films for domestic release offered a convenient way of turning a profit without incurring major production costs. Differences of language and culture, however, could stand in the way of audience enjoyment. While dubbing might help with the language issue, if never quite seamlessly, other forms of cultural difference continued to set audiences apart. For example, Americans raised on Hollywood fare tended to be unfamiliar with even the most popular of Japanese actors, a circumstance that led Allen to joke in Tiger Lily‘s opening credits that the movie starred “A NO STAR CAST.” The line was meant to be humorous, but in the end it differed little from the various publicity posters of the time that proclaimed that one or another kaijū eiga import featured a “JAPANESE CAST” (Fig. 1-01-011) or a “CAST OF THOUSANDS” (Fig. 1-01-012) without actually naming any. (As another part of this website explores, a common solution to the same dilemma in Italy was to lace the publicity for made-in-Japan movies with entirely made-up, yet Western-sounding, names.)

In What’s Up, Tiger Lily?, the best Woody Allen could do to add a familiar name to the cast was to solicit a sultry striptease from China Lee (Fig. 1-01-013), Playboy‘s first Asian-American centerfold model and at the time the girlfriend of Allen’s funnyman mentor, Mort Sahl. Again, Allen chose to have his cake as well as eat it, titillating viewers with a steamy display of “Oriental” flesh (stereotypically coded in the title of the movie, and on publicity posters [Fig. 1-01-014], as feline) while at the same time poking fun at American ignorance of East Asian geography. (It’s only fair to note that Lee’s first name is correctly pronounced “Chee-na.”) Similarly, by giving MIHASHI Tatsuya’s 008 character the very un-Japanese-sounding name of “Phil Moskowitz,” Allen hinted obliquely that there were limits to the interchangeability of racial, religious, and national identities even in the cosmopolitan world of cinema.

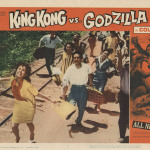

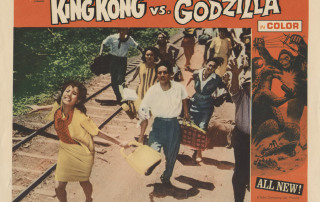

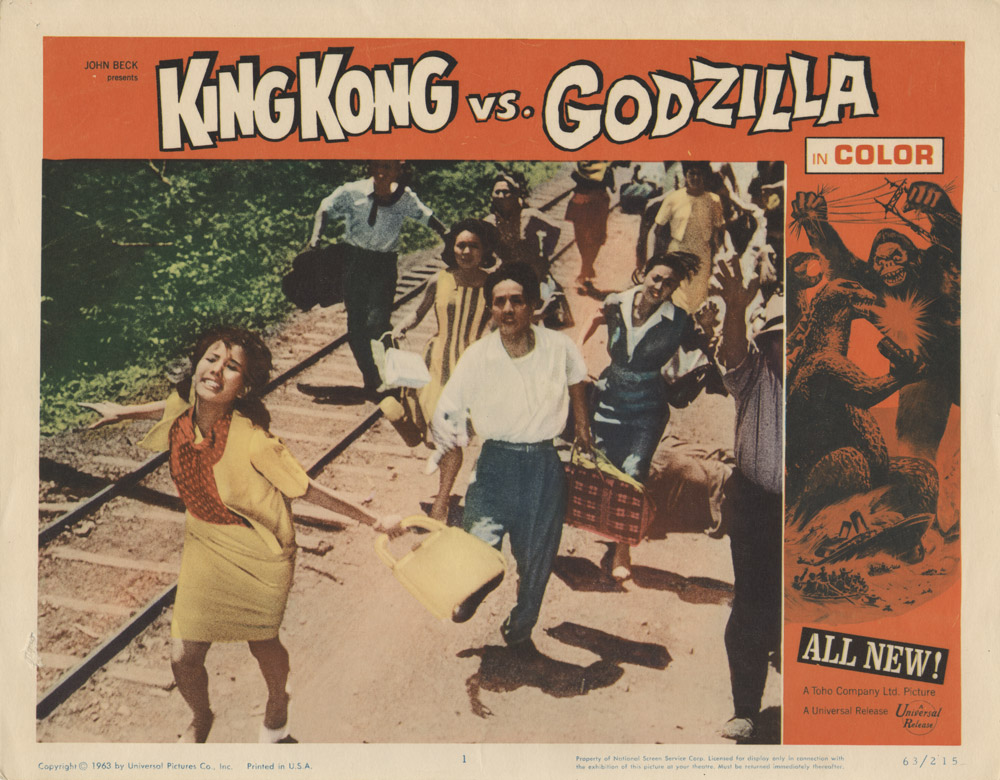

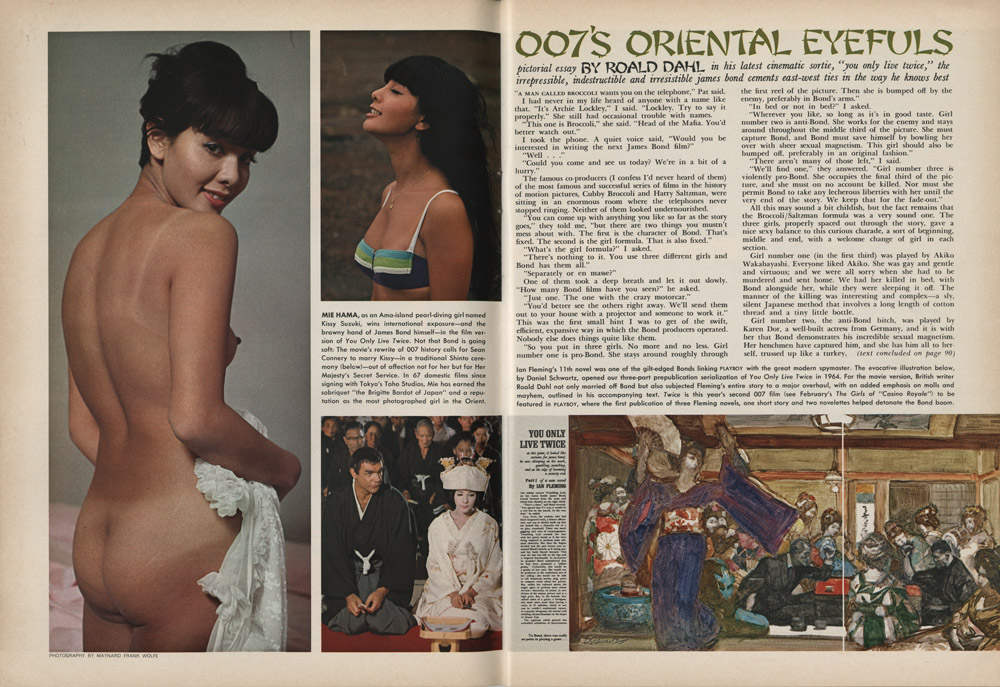

In fact, What’s Up, Tiger Lily? would never have been made were it not for an already established network of trans-Pacific film connections centered on Tōhō studios in Japan and American International Pictures in Hollywood, and bridged by such enterprising middlemen as Hank Saperstein. Much traffic in the kaijū eiga genre traveled along those same circuits. What’s Up, Tiger Lily? itself features a number of familiar faces from Tōhō’s monster films, conspicuous among them MIE Hama (born 1943) and WAKABAYASHI Akiko (born 1941)—Allen’s “Suki Yaki” (Fig. 1-01-015) and “Teri Yaki” (Fig. 1-01-016) respectively—whose acting credits include such kaijū classics as King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962; that’s Hama out in front of the pack in Fig. 1-01-017) and Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964; Wakabayashi’s on the left in Fig. 1-01-018). The two Tōhō actresses would soon become even better known to American moviegoers when, ditching 008 for 007, they appeared as Bond girls “Kissy Suzuki” (Fig. 1-01-019) and “Aki” (Fig. 1-01-020) opposite Sean Connery in 1967’s You Only Live Twice—as well as in a Playboy spread (Fig. 1-01-021) that raised eyebrows back home. That same year also saw Woody Allen play a role in a genuine, if in its own way parodic, James Bond film, 1967’s Casino Royale.

The same AIP-Tōhō-Saperstein connection that helped launch the career of Woody Allen led that of a different American celebrity, Nick Adams (1931–1968), down a more slippery slope from Oscar nominee to Hollywood has-been. Some have even seen it as a contributing factor in his early death. (“It hurt him,” claimed one Hollywood gossip columnist in 1968, that “most of his film offers seemed to come from Europe or the Orient” [Modern Screen]. “What else was left? …except death,” another Tinseltown pundit asked pointedly.) The Ukrainian-American actor with the trademark blond hair, familiar to a certain generation of TV viewers as Johnny Yuma of The Rebel (1959–1961; Fig. 1-01-022), undoubtedly pales before Sean Connery in the annals of cinematic espionage. But for Japanese audiences of the Sixties, he was at least a credible rival. 1967’s sequel to Key of Keys, which circulated internationally as The Killing Bottle (J. title: Zettai zetsumei; Fig. 1-01-023, Fig. 1-01-024), saw MIHAHI Tatsuya’s 008 character—”Phil Moskowitz,” in other words—team up with American secret agent “John Carter,” played by the nimble Nick Adams, to foil the assassination of the prime minister of “Buddhabal.” If you don’t recognize the name of the place, that’s to be expected, because “Buddhabal” was just the sort of “made-up but real-sounding country” that Woody Allen had mocked in the previous year’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (In terms of kaijū eiga geography, it presumably lies somewhere in the vicinity of “Selgina,” a Himalayan monarchy that similarly fell victim to Cold War intrigue in 1964’s Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, although the assassination drama involved a more literal kind of Third World in Ghidorah’s case.) On the other hand, the multinational security organization to which Mihashi’s and Adams’s characters belong has a consistently phony name in Japanese, but varies in English-language publicity materials between the fictional “International Secret Police” and the actually existing, and likewise Paris-headquartered, Interpol. Egg-salad smugglers, beware.

The Killing Bottle wasn’t the first movie in which Adams played American sidekick to a Japanese leading man. After his Hollywood fortunes began fading in the early Sixties, this contemporary and pal of James Dean found what almost amounts to a second career at Japan’s Tōhō studios, following an introduction made by UPA’s Hank Saperstein. From Tōhō’s perspective, bringing a Hollywood celebrity into the fold offered a means of injecting international color—or to put it another way, conspicuous whiteness—into made-in-Japan properties that it hoped would sell better as a result not just domestically but also overseas, and especially in the U.S., where the Japanese studio was eager to raise its profile.

Arguably, Adams’s first American-Japanese buddy picture wasn’t 1967’s The Killing Bottle but 1965’s Invasion of Astro-Monster (released by UPA in 1970 as Monster Zero; Fig. 1-01-025), the sixth entry in the Godzilla series. There, Adams had joined hands with TAKARADA Akira (born 1934) to preserve world peace and security not as a spy duo but as a pair of American and Japanese astronauts (Fig. 1-01-026). Suggestively, if none too imaginatively, their respective characters are named Glenn—evoking John Glenn, who in 1962 became the first American to orbit the Earth—and Fuji (written the same way as the iconic Japanese mountain). Since Takarada had played the romantic male lead in the original Gojira, one can scarcely imagine a more appropriate emblem of the cozy U.S.-Japan alliance that kaijū moviemaking at Tōhō had forged by the mid-Sixties. Whereas 1954’s Gojira had portrayed a complicated love triangle haunted by memories of World War Two, 1965’s Space Age bromance between “Glenn” and “Fuji” projected a conspicuously rosy picture of American-Japanese amity, unencumbered by either the historical past or by terrestrial rivals.

Those much younger than myself may find it difficult to believe, but there was once a place I like to think of—with no condescension intended—as Uncool Japan. Woody Allen made infamous fun of it in his 1966 spy send-up What’s Up, Tiger Lily? [VISUAL SIDEBAR 1: What’s Up with What’s Up, Tiger Lily?], with its hokey “Oriental” characters and intentionally inept dubbing. Nevertheless, by the time the comedy was released on home video in the early Eighties, one of Allen’s original 1966 gags showed serious signs of aging. In the Allen-scripted version of the film, a Yokohama cabbie, playing amateur tour guide, directs the attention of his passengers to a “world-renowned factory where the broken Japanese toys are made.” The joke was already a bit stale by the late Sixties; a decade and a half later, it was hopelessly outdated. By the early Eighties, Japan’s manufacturing prowess commanded considerable respect around the world—and on the strength of more than just toys—so that the once-prevalent notion that Japan-made goods were typically inferior in quality and less desirable than those produced elsewhere no longer resonated with the sensibilities of a younger-generation audience. Ironically, the most sophisticated equipment for watching the newly released videotape was by then most likely made in Japan and based on state-of-the-art Japanese technology.

Fast-forward a couple decades. By the turn of the millennium, made-in-Japan animated films, TV programs, comics, Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh! cards, video games, and other forms of soft merchandise had come to define and shape the latest trends in pop culture in many countries. Consumer Japanophilia especially grew during the Nineties, supposedly a “lost” decade for Japan’s national economy, but by no means in terms of creative output. Even after the millennium’s turn, the global popularity of Japanese mass-culture commodities has shown few signs of abating. Sanrio’s trademark Hello Kitty character still smiles her mouthless smile on stationery and knapsacks around the world; film directors and actors like MIYAZAKI Hayao and WATANABE Ken feel at home at the Oscars; and American teenagers freely use such terms as Kawaii (Japanese for cute) and Hentai (literally “perverted”—but more often used in the sense of sexually-themed) to refer to particular categories of manga and anime. In fact, the words anime and manga themselves hardly ever appear in italics anymore, having been fully incorporated into the English language. As Douglas McGray put it memorably back in 2002, Japan’s GNC or “Gross National Cool” has outstripped most of its rivals for quite some time now.

Almost every one of my students has known the Cool Japan literally since childhood. But the Uncool Japan that I grew up with is a distant and receding country. Fewer and fewer are those of us who were familiar as youngsters with those gimmicky giant monsters, known in Japanese as kaijū, who swam, crept, or flew their way into our everyday lives from the Land of the Rising Sun. In the days before CNN and the Internet brought the world into practically every home in so-called real time, the more innocent among us might even be forgiven for believing that Japan was home to actual monsters and not just to the smaller-statured men in rubber suits who played them. For an American tyke growing up in the Sixties, the archipelago of Japan was one vast Monsterland, not unlike the imaginary island preserve—strikingly similar in conception to Michael Crichton’s later Jurassic Park—that made its film debut in the 1968 kaijū extravaganza Destroy All Monsters. Why else would monsters display such a conspicuous fondness for attacking that particular nation’s cities?

Such childish misperceptions are less conceivable, of course, in the globalized and cyberlinked information community of the early twenty-first century. Other images of Japan have replaced them—images that may be truer to life, but that are equally a product of mass culture. For the Godzilla Generation, especially outside Japan, one of the most familiar views of Tokyo used to be a cityscape of tumbling buildings and panic-stricken crowds. By contrast, for today’s generation of Japanophiles, it’s not the footsteps of made-up monsters that imprint Tokyo’s sidewalks so much as the incessantly photographed and televised hordes of well-heeled and fashionable young women and men who stroll the trendy neighborhoods of Harajuku and Shibuya. Cool Japan, in other words, has all but replaced Uncool Japan in the popular imagination. Such is the malleability of perceptions in an age of global capitalism.

Yet from the perspective of a cultural historian, these two Japans—Cool and Uncool—are by no means opposites. Instead, they relate intrinsically to each other as complementary phases of a longer process. The bigger picture, which unfolds gradually across the latter half of the twentieth century and beyond, is one in which the products of Japan’s mass-culture industries have emerged ever more conspicuously onto the global marketplace, acquiring a steadily growing degree of favor among overseas consumers. Since the Fifties, Japan has come to be identified abroad increasingly in terms of its popular culture. One of the things this website sets out to demonstrate is that, within this process of making Japanese cultural commodities known around the world, Godzilla and his kaijū kinfolk played a historically significant and highly visible role.

Figure 1-02-001

This black-and-white postcard (Fig. 1-02-001) likely predates my birth in 1959, but offers a view of the College Theatre, where I saw some of my first monster movies from Japan, more or less as it appeared during my Sixties childhood. Although it’s no longer a working theater, the building that housed the cinema still stands outside the borough of Swarthmore in southeastern Pennsylvania. The College Theatre can be seen at the center of the postcard, with a white-columned neo-Georgian portico and detached marquee. In the present era of multiplexes, it’s hard to imagine that only one show at a time played in such a large auditorium. Seating capacity at the College Theatre, which opened for business in 1946, was 812.

Among the movies I watched at the College Theatre—most probably as part of a Saturday-morning double bill—was Frankenstein Conquers the World, Tōhō’s 1965 take on Mary Shelley’s classic monster tale. The disturbing countenance of FURUHATA Kōji’s boy-monster (at right in Fig. 1-02-002), the striking presence of a blond American actor (Nick Adams) within a predominantly Japanese cast; the genuinely creepy scene with the crawling hand (Fig. 1-02-003); and the contrived coincidence of the storyline (Nazi scientists ship the heart of Frankenstein’s monster to Japan, where it gets irradiated by the Hiroshima A-bomb blast and consequently mutates) all made a lasting impression. For kids who were primarily interested in fight sequences—for example, this one (Fig. 1-02-004) between Frankenstein’s monster and the kaijū Baragon—cultural particularities such as the thatched-roof farmhouse in the background could easily escape notice, or at least conscious reflection. Until recently, U.S. movie theaters routinely displayed sets of studio-issued publicity images like this one in and around their lobbies—hence the name “lobby card.”

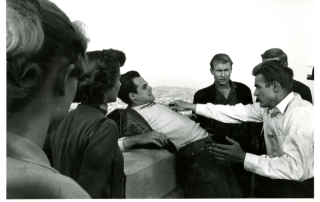

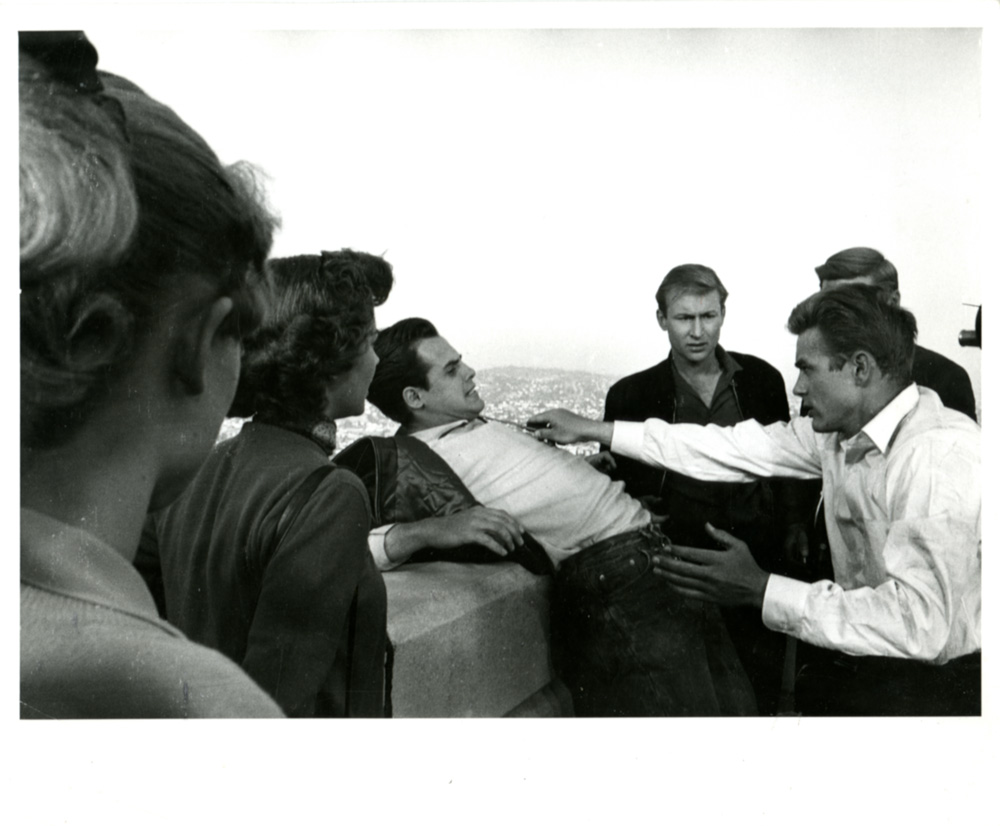

I could hardly have known it at the time, but I may have shared more with Nick Adams, the male lead of Frankenstein Conquers the World, than a Ukrainian-German heritage and an Eastern Pennsylvania birth. Adams’s sexuality has long been a matter of speculation, with sources of varying reliability claiming he was either gay or bisexual. Whatever the reality, the image that Adams presented for public consumption frequently played up his romantic connections with various leading ladies. Although we’ll likely never know and probably shouldn’t care whether Adams actually had an affair with James Dean, as some have alleged, the Hollywood publicity machine lavished considerable attention on his close friendship with Natalie Wood (in profile at left), who had played alongside both Dean (at right) and Adams (facing the camera) in 1955’s Rebel Without a Cause (Fig. 1-02-005). Adams’s career in Japan in the mid-Sixties coincided with the dissolution of his marriage to former child-actress Carol Nugent (Fig. 1-02-006), and gossip columns in Japan were quick to report that his onscreen romance with Tōhō starlet MIZUNO Kumi (born 1937), cast as Adams’s love interest in both Frankenstein Conquers the World (that’s Mizuno above in Figure 1-02-002, at left) and Invasion of Astro-Monster, was more than just an act. Adams’s relative shortness of stature, which may have handicapped his potential in Hollywood, made him an ideal recruit for filming in Japan, since he could add a Western complexion to the cast without upstaging any of the local talent. When paired with the six-foot TAKARADA Akira, his male Astro-Monster costar, Adams made for a distinctly diminutive sidekick—as this Italian poster (Fig. 1-02-007) reflects—thus visually reversing the geopolitical standing of their respective nations while at the same time conveying a sense of mutual dependency.

Witness my own history. My acquaintance with Godzilla began in the late Sixties, when Godzilla was already a teenager. In the suburban Philadelphia community where I grew up—as I suspect was the case in any number of similar towns across America—more than a few parents, especially those with young boys, welcomed a weekly respite from their boisterous kids and were all too happy to take turns shuttling them to the nearest movie house on Saturday mornings to be distracted for a few hours by a double-feature matinee [VISUAL SIDEBAR 2: Matinee Idylls]. The offerings with which the local theater tempted my contemporaries and me included, among other titles, Jules Verne fantasies and made-in-Britain horror flicks, along with miscellaneous Hollywood fare. Although most of the young viewers paid little attention to the national origins of a given feature, the playbill in fact sampled from several cultural traditions and international movie industries. Occasionally, Japanese productions, chiefly of the kaijū eiga (monster movie) variety, would enter the mix. I don’t recall how many such Japanese titles I saw in that setting or exactly which ones they were, but I know for sure the list included Frankenstein Conquers the World and Destroy All Monsters. Several scenes from those films made a particularly strong impression and have remained with me over the decades.

For example, I vividly remember the non-Caucasian features of the title figure of Frankenstein Conquers the World, released originally in Japan in 1965, and the fact that they seemed distinctly unconventional to my young eyes. By the same token, that visual difference made the character all the more eerie and unforgettable. At seven years of age or thereabouts, I’d already seen Western cinematic versions of Mary Shelley’s monster and knew what he was “supposed” to look like. Even today, FURUHATA Kōji’s troubled countenance is, along with that of Herman Munster from TV’s The Munsters—I’m a child of the Sixties, after all—one of the two faces of Frankenstein that I can call readily to my mind’s eye.

Figure 1-03-001

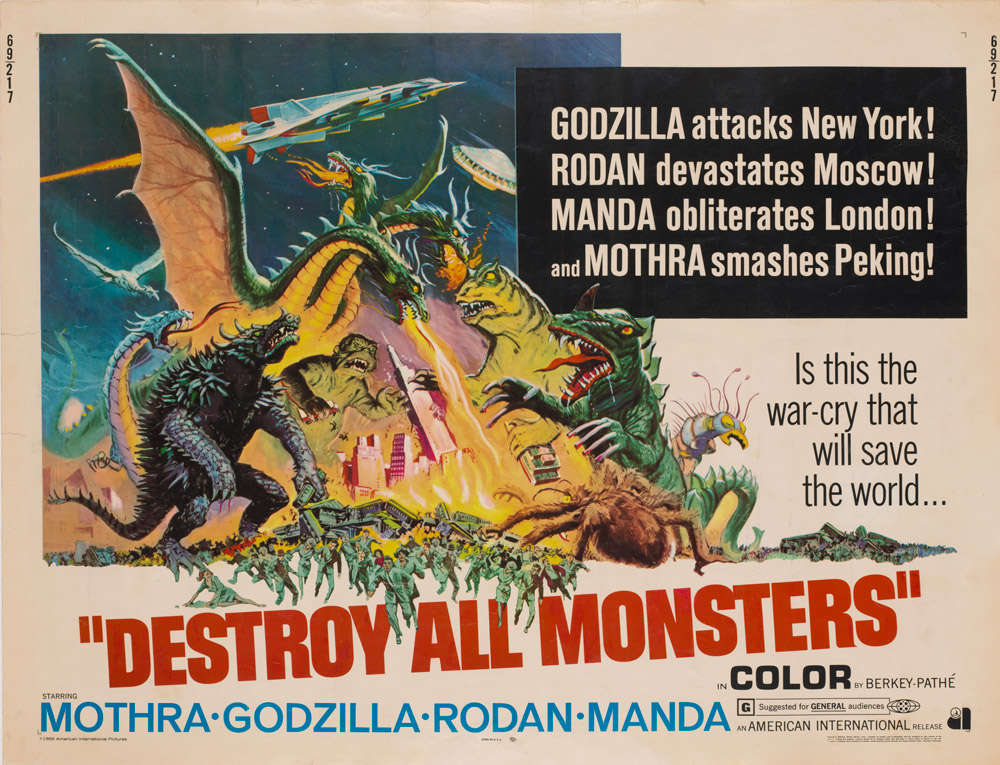

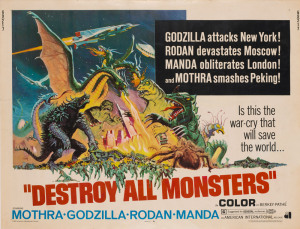

No matter where you sat along the Cold War ideological spectrum, the U.S. half-sheet poster (Fig. 1-03-001) for 1968’s Destroy All Monsters offered satisfying targets of destruction. One aspect of this itinerary of Cold War devastation puzzles me, however. Given Japan’s China policy at the time, shouldn’t Mothra have been smashing Taibei, the seat of China’s Nationalist government-in-exile, instead of Beijing, whose Communist regime the Japanese government hadn’t yet officially recognized? It wouldn’t be till 1972 that Japanese prime minister TANAKA Kakuei (he’s the black-suited man in Fig. 1-03-002) followed Mothra’s, as well as Richard Nixon’s, path to Beijing and set up full diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic. Unlike Mothra’s imaginary jaunt of 1968, Tanaka’s 1972 visit to the mainland had measurable political consequences. In either case, though, cinema helped mold the everyday perceptions of Cold War audiences. Viewers in Thailand could watch a documentary highlighting the Tokyo-Beijing rapprochement—together with other glimpses of “today’s China”—from the same seats where they had witnessed a made-in-Japan Mothra wreak havoc on the mainland Chinese capital just a few years previously (Fig. 1-03-003).

Around a divided Cold War world, the kaijū eiga genre offered a hopeful vision of planetary unity that numbered among its distinct viewing pleasures. The imaginary threat of globe-roaming monsters and extraterrestrial aliens reminded audiences of their shared humanity, even as it provided uplifting fictional examples of terrestrial solidarity across boundaries of nation, race, religion, and ideology—at times even species identity. What’s more, kaijū films gave viewers the opportunity to experience such dire, yet at the same time community-affirming, scenarios without actually exposing them to physical danger. Whether, and for how long, such a flickering sense of global citizenship would survive beyond the theater exit is, of course, not so easily gauged. Still, the sheer number of people who watched kaijū eiga across the decades, along with the fact that the genre’s audience skewed toward a younger and hence all the more impressionable demographic, suggests that the collective impact could hardly have been negligible. As such, the history of the kaijū eiga is, at least in part, the history of an emerging planetary consciousness, a process that Module 6 of this website will explore in more detail.

I watched with equal fascination as Destroy All Monsters showed my friends and me a larval Mothra “smashing” Beijing—or Peking, as we used to call it in those days before ping-pong diplomacy [VISUAL SIDEBAR 3: Kaijū Diplomacy]. My mother and grandparents fled the Soviet Union during the 1940s, so the map of Cold War geopolitics held a more personal interest for me as a child than it did for many of my playmates. It was thrilling to see onscreen a tantalizing, if imaginary, glimpse of “Red China,” a place I knew my passport prevented me from visiting in real life. Unlike most Hollywood pictures I’d at that point been exposed to, Destroy All Monsters, a flick from Japan, transported me instantly to one of the few places on earth in 1968—the year that first elected Nixon—that seemed even more distant and otherworldly than Japan itself. The scene of Mothra slinking along the railroad tracks to Beijing evokes wistful feelings even as an adult.

Figure 1-04-001

Figure 1-04-002

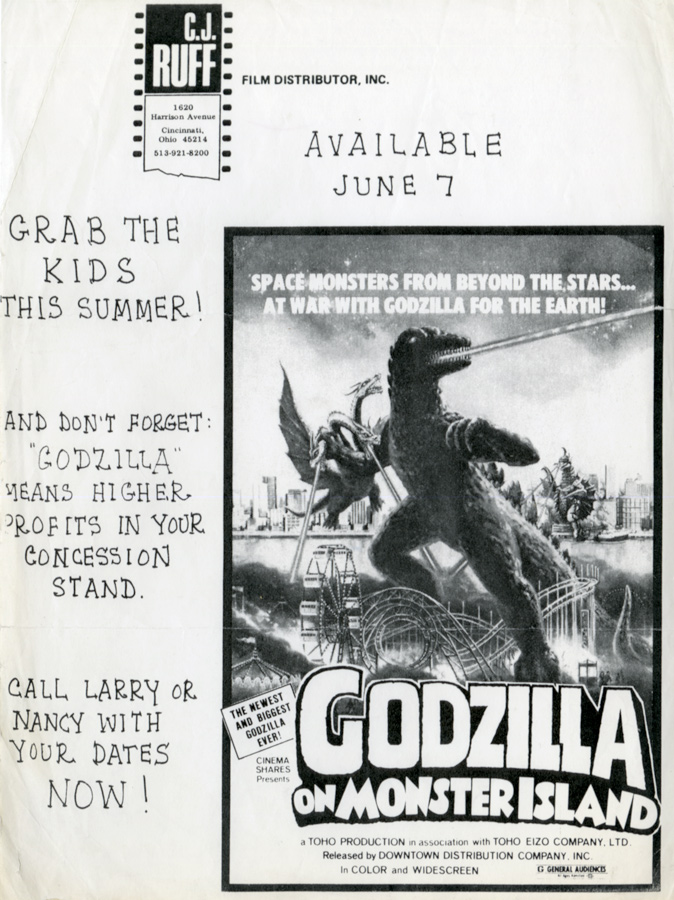

American promoters clearly recognized the appeal that “Monster Island” held for Cold War kids like myself. Inspired by the success of Destroy All Monsters (1968) and All Monsters Attack (1969; U.S. title: Godzilla’s Revenge or Minya: Son of Godzilla), both of which featured extended segments on the island, publicists in the U.S. came up with the title Godzilla on Monster Island for a film now more commonly referred to as Godzilla vs. Gigan (1972). The choice of name blatantly ignored the fact that monsters’ island home appears only in a few minutes of stock footage. The artwork of the 1978 U.S. publicity poster (Fig. 1-04-001) for Godzilla on Monster Island shows what is clearly an amusement park. A black-and-white version of the scene appears also on a promotional flyer (Fig. 1-04-002) circulated by an Ohio-based film distributor.

In fact, the locale depicted here isn’t Monster Island at all; instead, it’s the Japan branch of an imaginary “World Children’s Land,” where a good part of the film’s action takes place. Coupled with the artwork, the American title of the movie easily conveys the impression that Monster Island is sort of like a Japanese version of Coney Island, complete with roller-coaster ride. In real-world terms, of course, it’s movie theaters that share a greater similarity with amusement parks, since, as “Larry” and “Nancy” note, concession-stand sales were and remain an important component of business revenue in the children’s-entertainment industry.

1993’s Jurassic Park, the first installment of what has since become a larger Hollywood franchise, arguably offers a more high-tech film vision of humans and monstrous saurians sharing the same artificially controlled—yet also easily uncontrolled—Pacific-island habitat, evocative of a theme park. But the core idea was already there in 1968’s Destroy All Monsters, although that earlier film’s Monsterland / Monster Island, despite its fictional “1999” setting, reflected the analog imagination of the Sixties, whereas Jurassic Park‘s Isla Nublar (supposedly located off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica) cashed in on an emerging public fascination with biotech and digital electronics, including computer-generated imagery, that was more in tune with the Nineties as they actually developed.

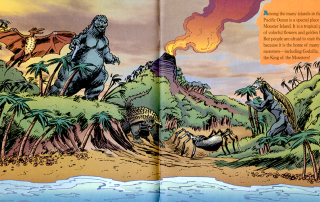

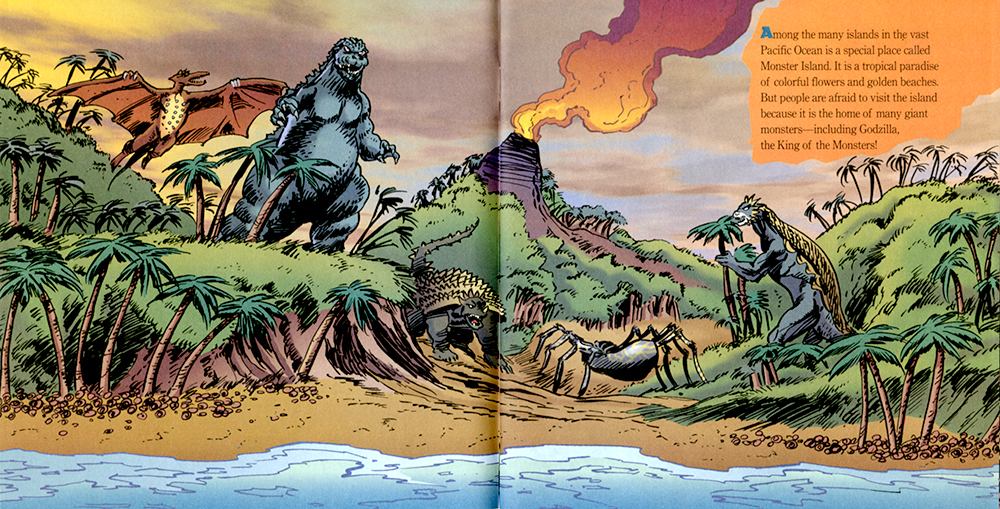

Figure 1-04-003

In a curious case of global warming, the climate of Monster Island also came to resemble Isla Nublar increasingly over the years. Whereas Destroy All Monsters had identified the kaijū paradise as part of the subtropical Ogasawara chain (as illustrated in Figure 2-02-009, to be examined in the next module), representations from later in the century, such as Jacqueline Dwyer’s Tōhō-licensed but U.S.-published children’s book Godzilla on Monster Island (1996; Fig. 1-04-003), were more likely to drape the island in verdant equatorial hues. In some cases, Jurassic Park may have provided direct inspiration for the tropical makeover; indeed, the American producers of Godzilla: The Series (1998–2000) went so far as to rename their TV version of Monster Island “Isla del Diablo.” But the warming trend may also be seen as a reversion to the kaijū geography of the early to mid-Sixties (that is, prior to 1968’s Destroy All Monsters), in which such fictional South Sea isles as the sun-drenched Solgel—referred to explicitly as an “island of monsters” (kaijūtō) in 1967’s Son of Godzilla—had played a conspicuous role as kaijū breeding grounds.

Similarly unforgettable in Destroy All Monsters were the scenes of Monsterland, more familiarly known as Monster Island [VISUAL SIDEBAR 4: Monster Archipelago]. According to the movie’s plot, by 1999 all the earth’s kaijū had been pacified and brought to live together in this isolated, semitropical preserve. Despite its monstrous megafauna, the island setting seemed idyllic—sort of like Milton’s Paradise on steroids. For some reason, I concluded that Monster Island was supposed to lie in the Caribbean, perhaps inside the Bermuda Triangle. I may not have been paying sufficient attention to the film’s narration, but at least my imagination was healthy.

As I recall these episodes from boyhood, it occurs to me that my interest in kaijū eiga was a bit more brainy than hormonal even then. I was bookish rather than boisterous as a child. The spectacle of Japanese monsterdom attracted me less on account of its staged violence and pyrotechnics, which appeared the biggest draw for some of my schoolmates, than because of the lesson in geography and pseudo-geography that it provided. I’m struck, too, by an underlying paradox. Staring at the screen in that darkened theater just outside the municipal limits of Swarthmore, Pennsylvania, I was clearly aware that the feature films I was watching were Japanese in origin, as were most of the actors who played in them. On another level, though, the movies could well have been—and in a very real sense were—taking place in my own backyard. In order to experience the sort of ticklish fear that constitutes one of the chief pleasures of watching a monster movie, one had to be able to imagine oneself among the creature’s possible victims, to place oneself, in effect, among the nameless crowds who flee in terror before the kaijū‘s approach. Geographic distance and cultural difference were immaterial in that moment, and Japan could seem, temporarily at least, just as close and familiar as the Jersey Shore. In my boyish mind, then, the movies I was viewing both were and weren’t Japanese. One might say this website illustrates basically the same point, albeit from a more mature and historically informed perspective.

All the above events transpired long before I came to study Japan in any serious way. And I can’t truthfully say that my early and relatively sparse encounters with its monsters were what led me in that direction. It was somewhat in the manner of an afterthought that I realized, just over a decade ago, that the products of Japanese culture to which I’d first been exposed weren’t the delicate verses by tenth-century court nobles that I learned to appreciate in college, although it was, to be sure, the latter that encouraged me to study the Japanese language. Nor did my introduction to Japan come by way of exquisite Tokugawa-era woodblock prints, as it did, famously, for the Impressionist painters and along with them many members of the nineteenth-century European public. Rather, the first form of Japanese creativity to reach the threshold of my consciousness was more kitschy and raucous than it was refined and sensitive. It was oversized rather than miniature, mass-produced not handmade, more future-looking than traditional. I began to wonder, as both a student and an object of history, what processes had brought that particular version of Japanese culture to my doorstep, and to that of a whole generation. This website presents some of the answers I’ve discovered, and some of the observations I’ve made along the way.