CONTINUED FROM MODULE 1 PART 1

GODZILLA AND THE GLOBE

One of the premises of this website is that Godzilla’s international circulation from 1954 through the present offers a concrete example of the historical process we call globalization. The term means different things to different people, and deserves explanation from the start. In a general way, globalization refers to an ongoing phenomenon in which national borders grow more porous and penetrable, owing to a complex set of economic, political, and technological factors exemplified by the emergence of multinational corporations, international regulatory bodies, and digital telecommunications. For some, globalization is a bad word, conveying a sense of unfettered corporate greed and American (or perhaps Northern Hemisphere) neocolonialism—but it’s not my immediate purpose to judge the ethical dimensions of the debate. Instead, I seek to add historical depth and geographic specificity to our understanding of evolving global interconnectedness, which may in turn allow us, or perhaps our descendants, to appreciate the process in more palpable ways. More specifically, I attempt in this website to sketch out some of the visible manifestations of globalization as it has shaped, for both children and adults, the world of fantasy and the imagination.

Monster movies provide a useful, if somewhat unconventional, lens for understanding the cultural dynamics of the globalization process. At least five factors make that the case. One is the nature of the cinema medium itself, which, as film scholars are fond of pointing out, has always been international. From the outset of filmmaking at the end of the nineteenth century, the technologies, personnel, esthetic styles, and genre conventions that make up this quintessentially modern art form have crossed geographic boundaries with conspicuous ease. Not only have moviemakers tended to be a cosmopolitan lot, but movie audiences, too, have grown accustomed to traversing borders while sitting in the comfort of their theater seats and armchairs. Hollywood’s traditional dominance over the domestic U.S. film market may seem an exception to the latter rule. In fact, though, Hollywood itself has long operated on a transnational basis with respect to financing, production, distribution, and profits. Even films made by Hollywood studios frequently feature shooting locations overseas. In a very literal sense, they shape the worldviews of their audience no matter where it may be happen to be watching.

Figure 1-05-001

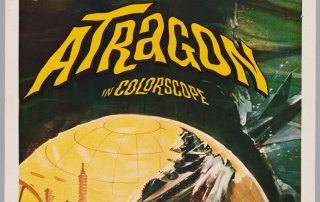

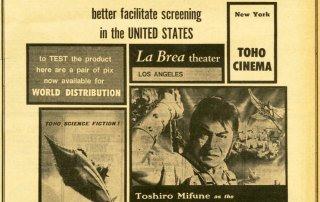

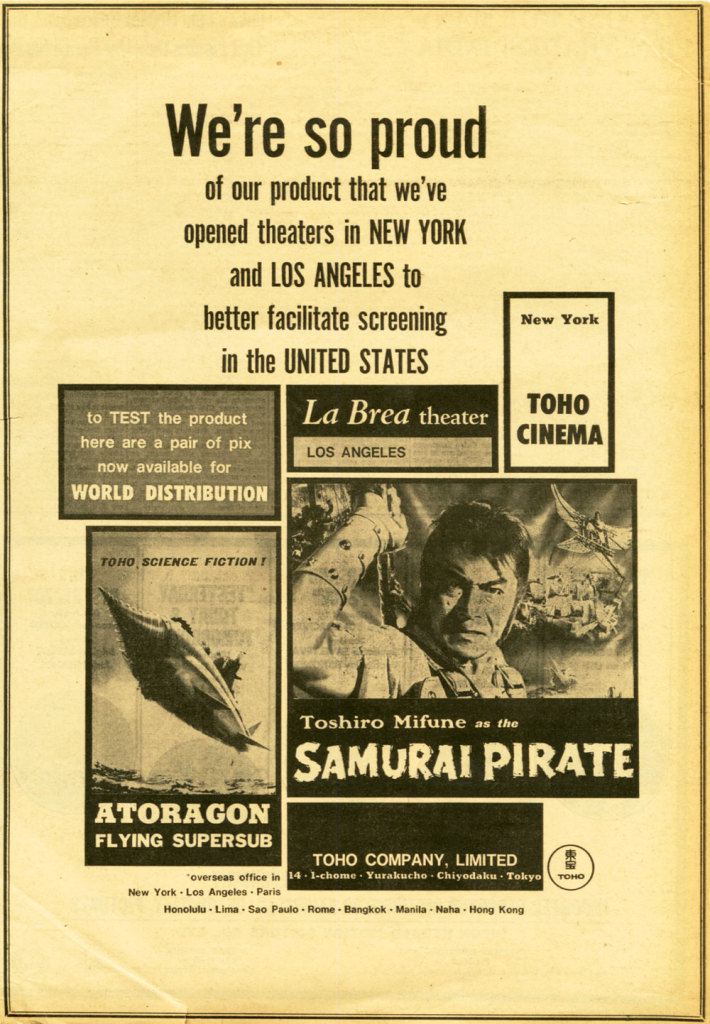

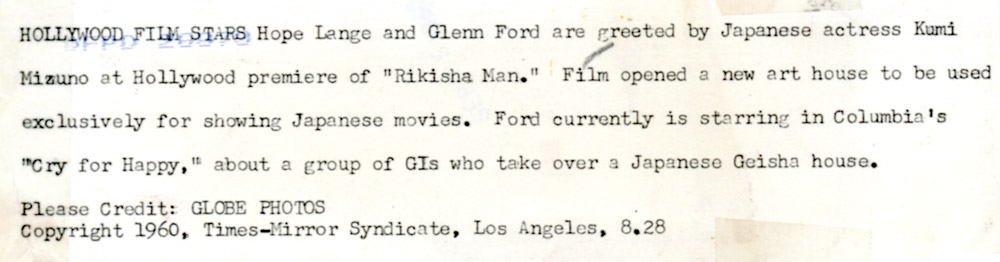

A 1964 trade advertisement (Fig. 1-05-001) proudly broadcasts the high expectations that the Japanese studio Tōhō had come to place on its international business one decade after introducing the kaijū eiga genre.

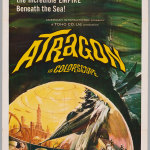

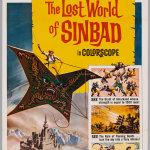

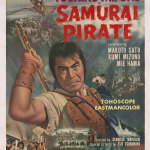

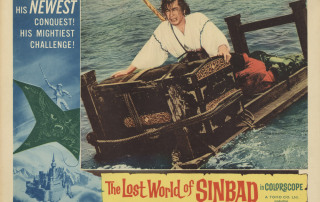

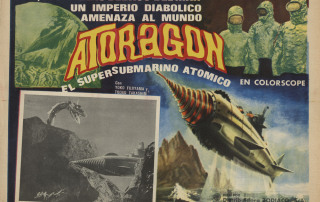

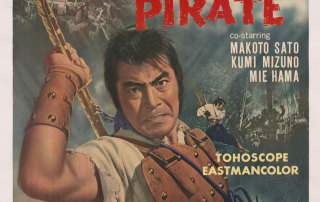

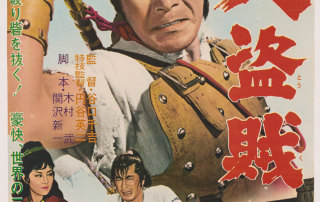

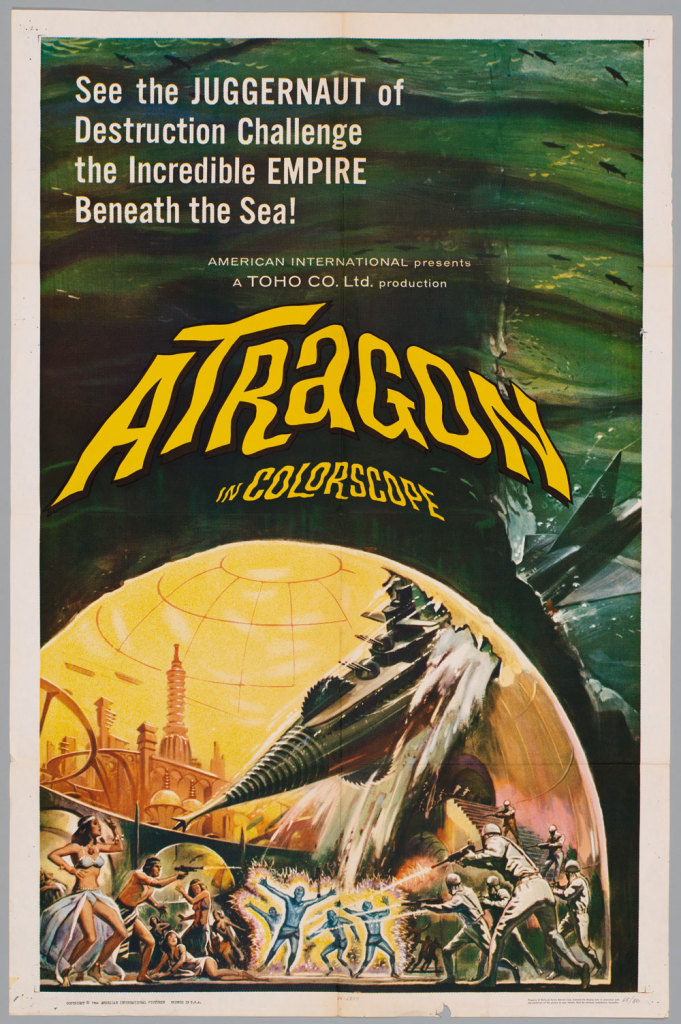

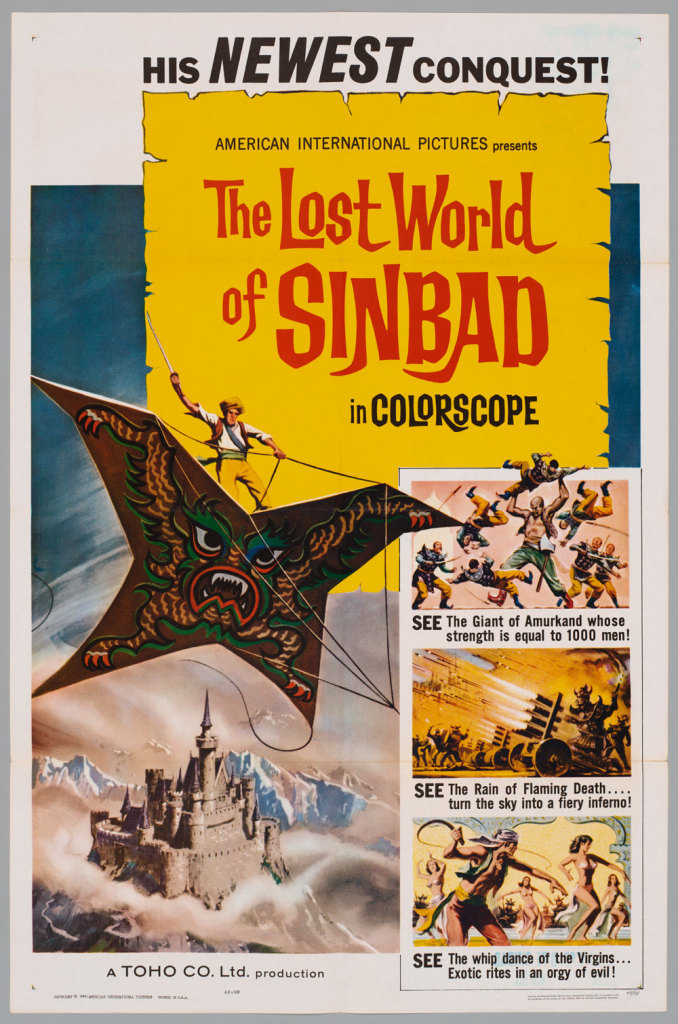

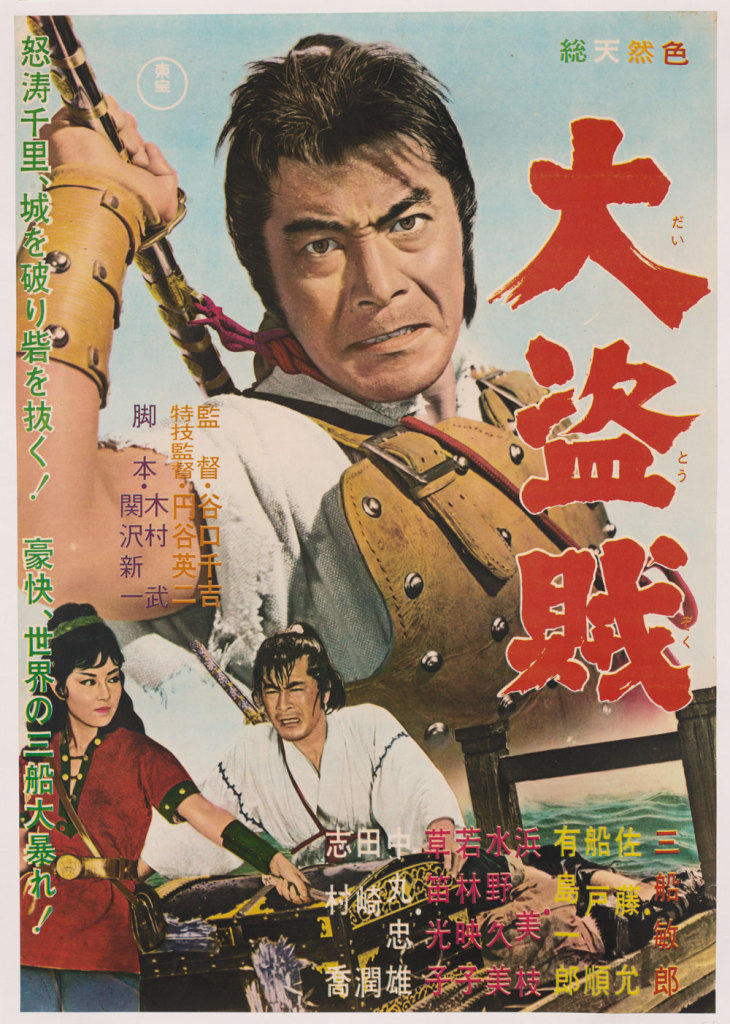

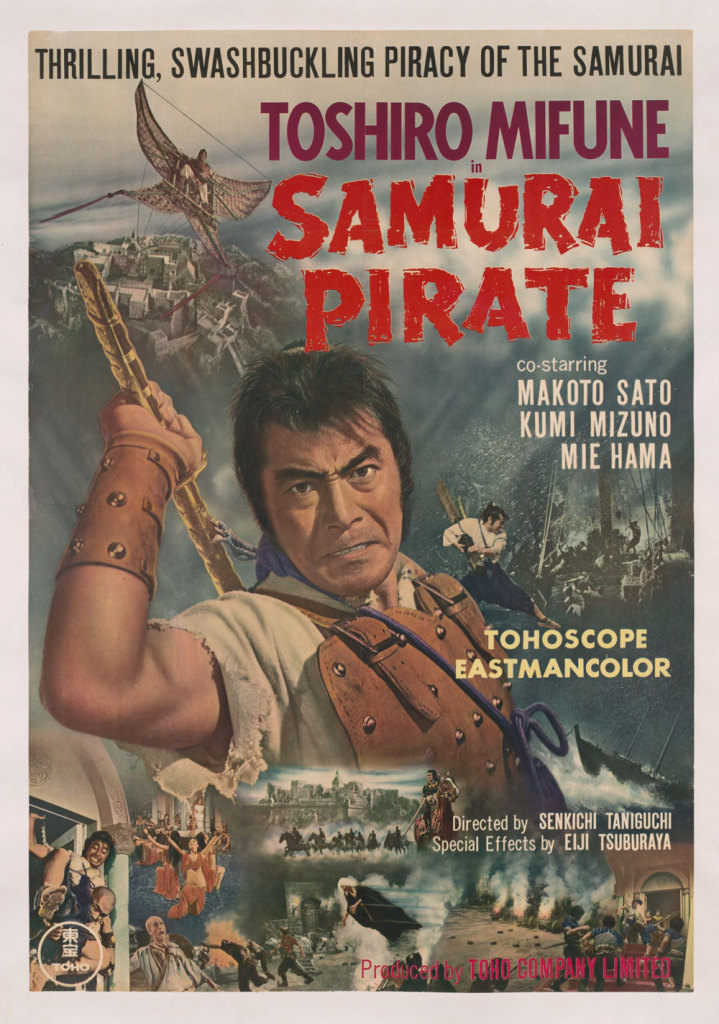

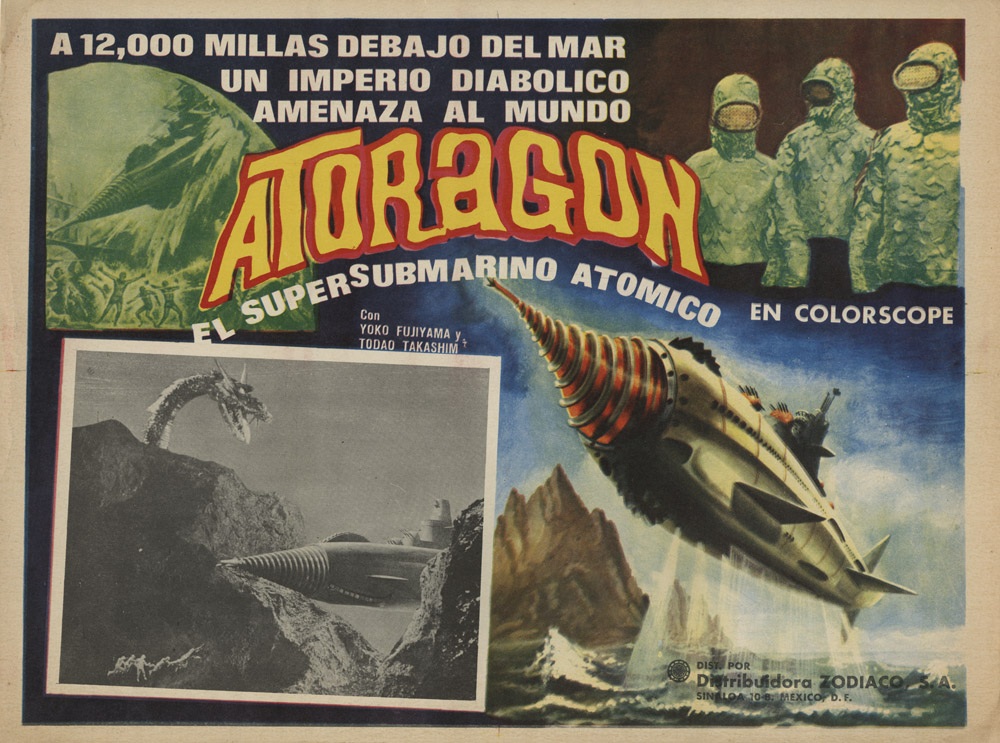

The special-effects features Atoragon, Flying Supersub (J. title: Kaitei gunkan; Fig. 1-05-002) and Samurai Pirate (J. title: Daitōzoku; Fig. 1-05-003), both made in 1963, would eventually play more broadly in the U.S., but only after receiving new dubs and under different titles. American International Pictures bought the North American and British Commonwealth distribution rights to both these Tōhō productions for $180,000, repackaging them in 1965 as Atragon (Fig. 1-05-004) and The Lost World of Sinbad (Fig. 1-05-005) respectively. Although the name Atoragon survived in a few markets—for example, in Mexico (Fig. 1-05-006)—viewers elsewhere around the world knew the film by such titles as Atragon and Ataragon (Fig. 1-05-007). Tōhō had come up with the clunky international-release title by combining the first letters of “Atlantis” and the last letters of the English word “dragon” (transliterated in Japanese as Atorantisu and doragon) so as to reflect that fact that the storyline involves a sunken continent guarded by a serpent kaijū. Whatever sense it may have made to Japanese ears, Western audiences were unlikely to make such a connection, since in English and other European languages, the L of “Atlantis” and the R of “dragon” are two different sounds. Conversely, Atragon, the adapted title that American International Pictures eventually chose, was just as unlikely to have originated in Japan, since the Japanese language typically alternates consonants with vowels and thus has no TR or TL combination.

Whereas linguistic differences challenged the promoters of Atoragon, Flying Supersub, it was a different form of cultural unfamiliarity that prompted the transformation of Samurai Pirate (Fig. 1-05-008) into The Lost World of Sinbad. These days, when imagery from Japan so saturates youth culture, it’s hard to imagine any American kid being unfamiliar with the figure of the samurai, but back in the Sixties, such was often the case. The word “samurai” meant little to me until the mid-Seventies, when comedian John Belushi’s recurring character Futaba on TV’s Saturday Night Live took a cinematic stereotype once known only to art-house aficionados and brought it down to a popular level. I met my first samurai in such SNL comedy skits as “Samurai Delicatessen” (1976), although I hardly knew at the time that Belushi was channeling MIFUNE Toshirō as directed by KUROSAWA Akira. Whereas Belushi lived in Manhattan, amidst highbrow movie houses and sophisticated cinemaphiles, I was a teenager from the suburbs, and Belushi’s TV antics—like cutting down salami and slicing tomatoes with a samurai sword—seemed bizarre and funny enough even without fully understanding the source of the parody. A decade earlier, both “Samurai Pirate” and “Samurai Delicatessen” would have sounded equally like gobbledygook.

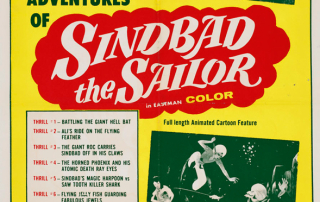

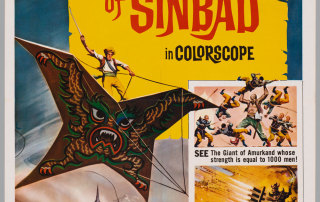

Americans were long acquainted, on the other hand, with the figure of the pirate, whose popular image had evolved in nineteenth-century fiction (notably Stevenson’s 1883 Treasure Island) and, with the emergence of cinema, quickly become a Hollywood staple. Rather than dilute the promise of pirate spectacle with a puzzling Japanese qualifier, AIP promoters chose to substitute a more familiar kind of foreignness and cast lead actor MIFUNE Toshirō, retroactively, as the legendary mariner Sinbad (Fig. 1-05-009). It mattered little that Mifune’s original character sailed the seas not of Araby but of Southeast Asia, being based on a historical Japanese trader of the sixteenth century. What was more important was that Sinbad had a name that even xenophobic Americans could recognize. Sinbad fit the bill especially well for marketing purposes, since Stateside audiences were already likely to associate that character with impressive special-effects photography, most memorably that of Ray Harryhausen (1920–2013), whose stop-motion “Dynavision” had made eyes pop in 1958’s The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (Fig. 1-05-010). Harryhausen was also responsible for the visual effects of 1953’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms—more on which in Module 4—which provided a direct inspiration for the following year’s Gojira.

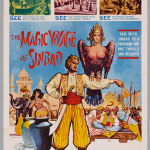

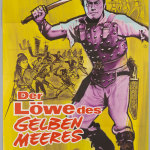

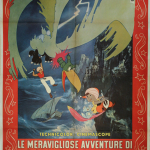

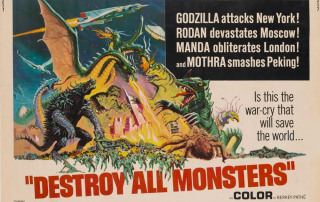

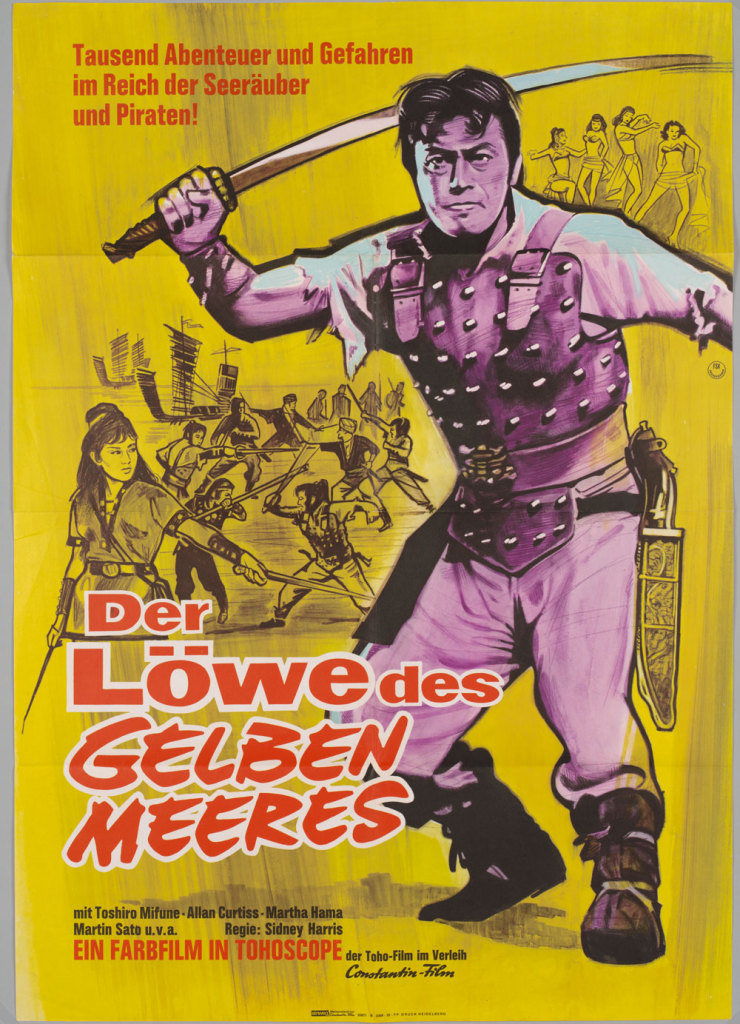

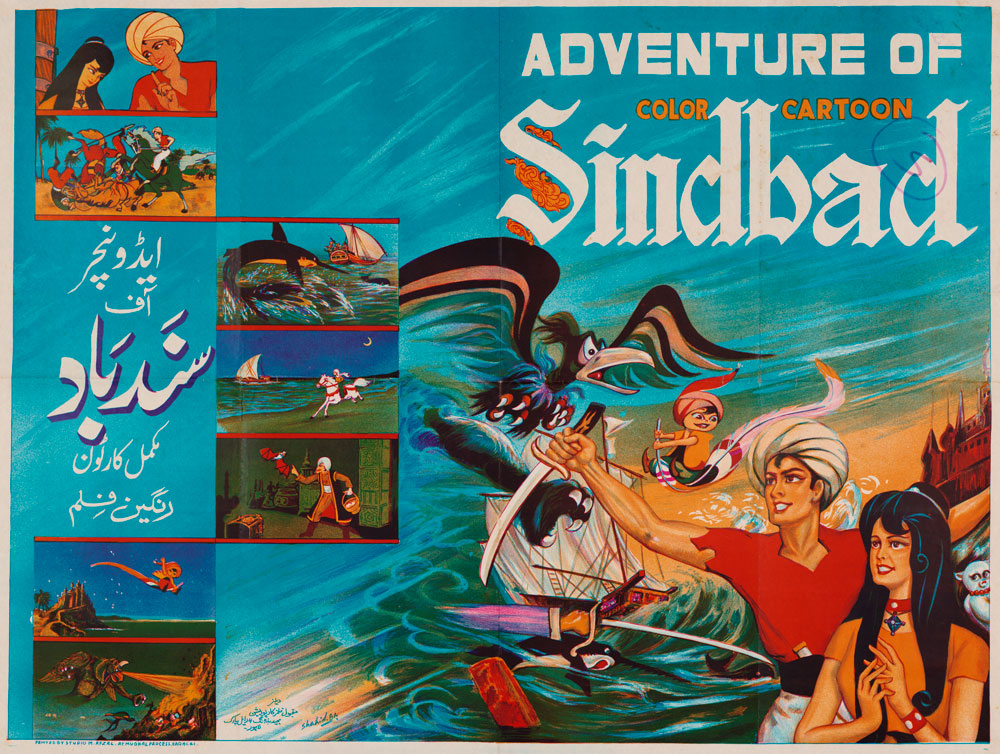

From a twenty-first-century perspective, it may seem ironic that invoking the Middle East instead of Japan could make American audiences feel more at home. But The Lost World of Sinbad wasn’t the first case in which a superficial Sinbad-ization had helped to disguise more alienating forms of foreignness. In 1962, Roger Corman’s Filmgroup had used the same formula to get Commie-hating American audiences to watch the USSR-made Sadko (1953; Fig. 1-05-011), with special effects by Alexandr Ptushko (1900–1973), sometimes called the “Soviet Walt Disney.” Ptushko’s live-action fantasy played in the U.S. as The Magic Voyage of Sinbad (Fig. 1-05-012), its script “adapted” (which is say, shorn of Russian references) by none other than the young Francis Ford Coppola. In both cases, promoters counted on a well-known Arabian legend to draw what might otherwise be reluctant viewers into the theater, although few audience members would remain fooled once Russian church spires or Japanese faces started to appear onscreen. West German promoters hit the mark closer geographically, but were no less prone to racial stereotyping, when they released Samurai Pirate under the title “The Lion of the Yellow Sea,” complete with a poster (Fig. 1-05-013) of the same yellow hue. Only in the realm of animation did Middle East and Far East come together more seamlessly: 1962’s Sindbad the Sailor (J. title: Shindobaddo no bōken), from the pioneering Tōei studios, concealed its Japanese origins as much onscreen (for example, by darkening the skin of its hero) as in its overseas poster art, whether it was playing in Euro-American markets like Spain (Fig. 1-05-014) and Italy (Fig. 1-05-015) or in Pakistan (Fig. 1-05-016), which lies close to Sinbad’s ancient birthplace. Promoters in the U.S. (Fig. 1-05-017) went so far as to endow the story’s legendary phoenix with “ATOMIC DEATH RAY EYES,” a trait that would have horrified (and not in a good way) audiences in Japan.

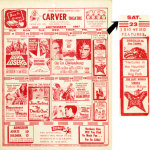

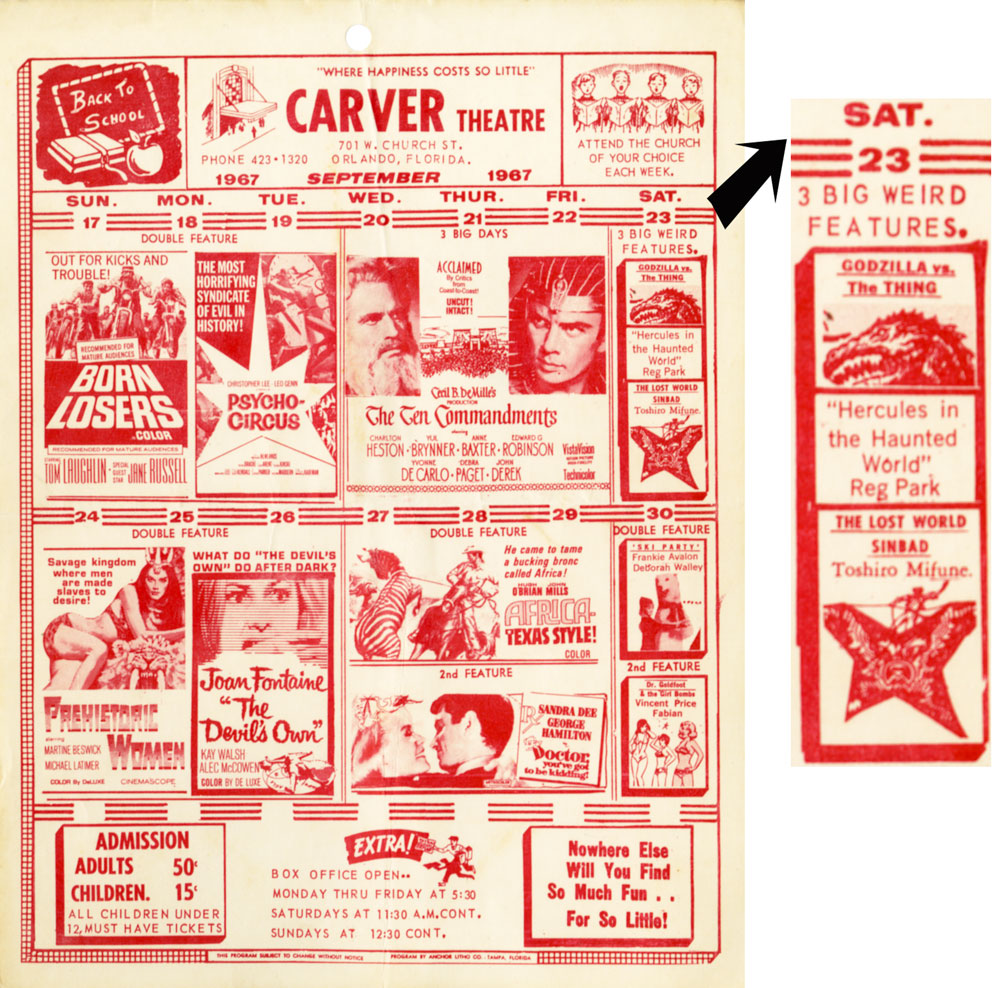

Since AIP specialized in the youth market, its movie releases, including Atragon and The Lost World of Sinbad, tended to fill the bill at theaters and drive-ins that were considerably more down-to-earth than the sophisticated metropolitan venues that Tōhō proudly showcased in its 1964 ad. The September 1967 calendar (Fig. 1-05-018) of a predominantly African-American movie house in Orlando, Florida, for example, lists The Lost World of Sinbad among the “3 BIG WEIRD FEATURES” that the management planned to screen one Saturday to attract the “Back To School” crowd. (If you followed the theater’s advice, you could atone for all that weirdness by attending “the church of your choice” the next morning.) Also listed on the night’s program was Godzilla vs. the Thing (1964), the AIP-dubbed version of Godzilla’s fourth film outing, otherwise known as Mothra vs. Godzilla.

Although Tōhō’s proud trade ad of 1964 gives Honolulu just passing mention, some of the first American theaters to show Japanese films were in fact located in Hawaii. Serving the islands’ large population of Japanese Americans, they began operating in the territory as early as the 1930s, well before Hawaii achieved statehood in 1959. Like their film programming, the publicity materials circulated by such ethnic theaters typically featured no less Japanese than English, as is the case, for example, with this printed fan (Fig. 1-05-019) from the late Fifties. It’s a souvenir of the Nippon Theatre, which opened its doors in 1948 on the corner of Keeaumoku and Beretania Streets near Honolulu’s Chinatown. One face of the fan advertises Sora yukaba (1957), a kamikaze-themed drama from Japan’s Shōchiku studios; the reverse (Fig. 1-05-020) promotes a locally manufactured brand of soy sauce, hinting at the ethnic makeup of the target audience. The original 1954 Gojira may very well have played at Japanese-language theaters like this one in Honolulu before it ever received an English-language soundtrack.

Between 1964 and 1976, Tōhō operated its own showcase theater in Honolulu. With a distinctively styled marquee perhaps meant to evoke a Japanese bridge or the gate of a Shinto shrine, the 760-seat Toho Theatre (in Japanese, Tōhō Gekijō) greeted passersby at 1646 Kapiolani Boulevard, now the site of a Papa John’s pizza restaurant. Exclusively featuring Tōhō productions, the theater’s playbill competed with Shōchiku fare at the Nippon and Daiei offerings at the Kokusai. Tōhō pulled out all the stops in launching its new million-dollar showplace on July 1st, 1964. Along with the studio president, it sent nine of its biggest stars—including SAHARA Kenji (born 1932), a familiar face for kaijū eiga fans—to attend opening-night festivities in Honolulu, which a local paper described as having “all the splash of a Hollywood pageant.” The picture that the Toho Theatre chose to screen that evening, by invitation only, was Samurai Pirate, that same special-effects swashbuckler with MIFUNE Toshirō that had appeared so prominently in the studio’s trade ad above. What Honolulu patrons saw was the Tōhō-dubbed international version of the film, rather than the AIP-edited Lost World of Sinbad, which wouldn’t be released until the following spring.

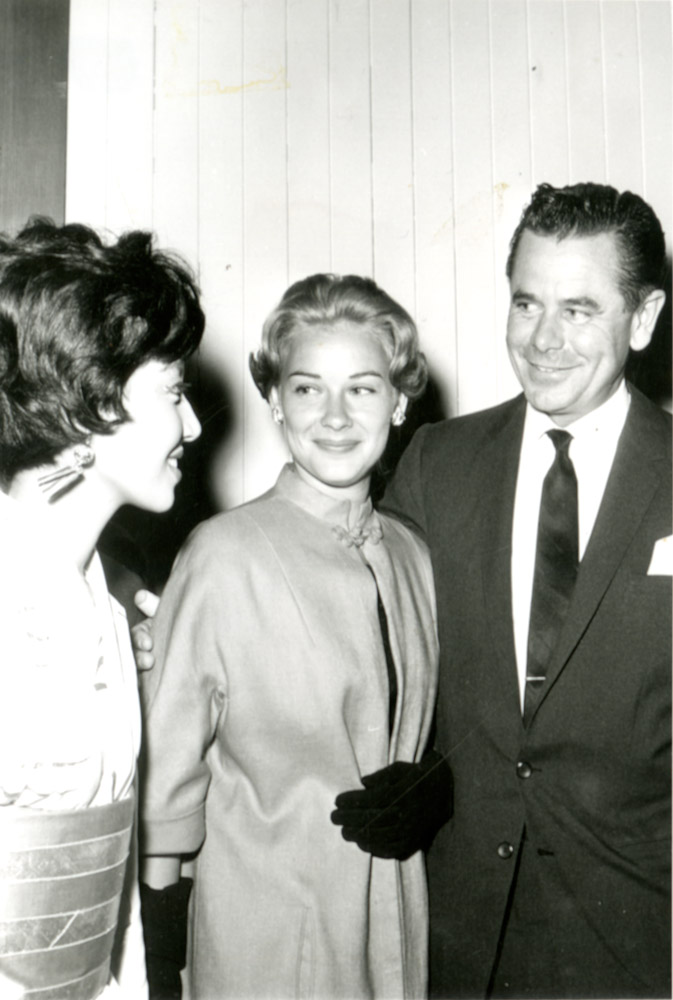

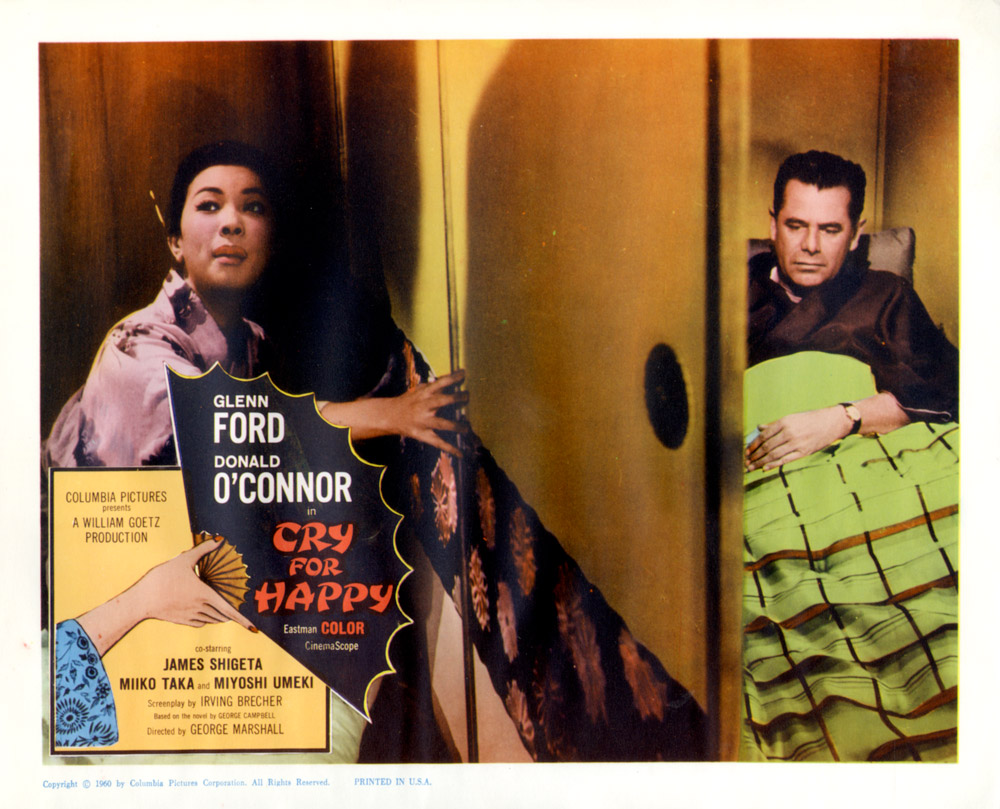

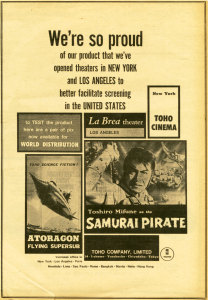

During Tōhō’s most aggressive phase of international expansion from the Fifties into the early Sixties, the studio prioritized the establishment of business offices and cinemas in three types of overseas location: (1) nearby Asian markets, (2) Western Hemisphere cities with large populations of Japanese migrants, and (3) major hubs of global film culture. Honolulu and San Francisco fit into the second category, New York into the third, and only Los Angeles into both. In L.A., Tōhō films ran at the La Brea Theatre at 857 South La Brea Avenue, which currently houses a Korean church. An announcement (Fig. 1-05-021) in the Los Angeles Times gives the opening date as August 5th, 1960. As a press photograph (Fig. 1-05-022) records, the inaugural event drew both Japanese and Hollywood film celebrities, including Glenn Ford, Hope Lange, and Tōhō starlet MIZUNO Kumi, who would become a kaijū eiga regular, and allegedly Nick Adams’s girlfriend, in just a few more years. Strikingly, the photo’s caption (Fig. 1-05-023) devotes as much attention to the upcoming Hollywood production Cry for Happy (1961; Fig. 1-05-024), set in Japan and starring Glenn Ford, as it does to the imported films offered at the La Brea.

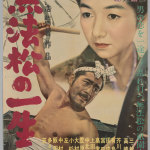

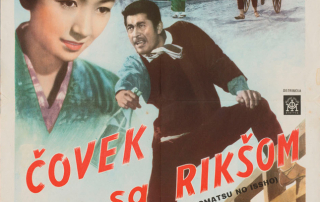

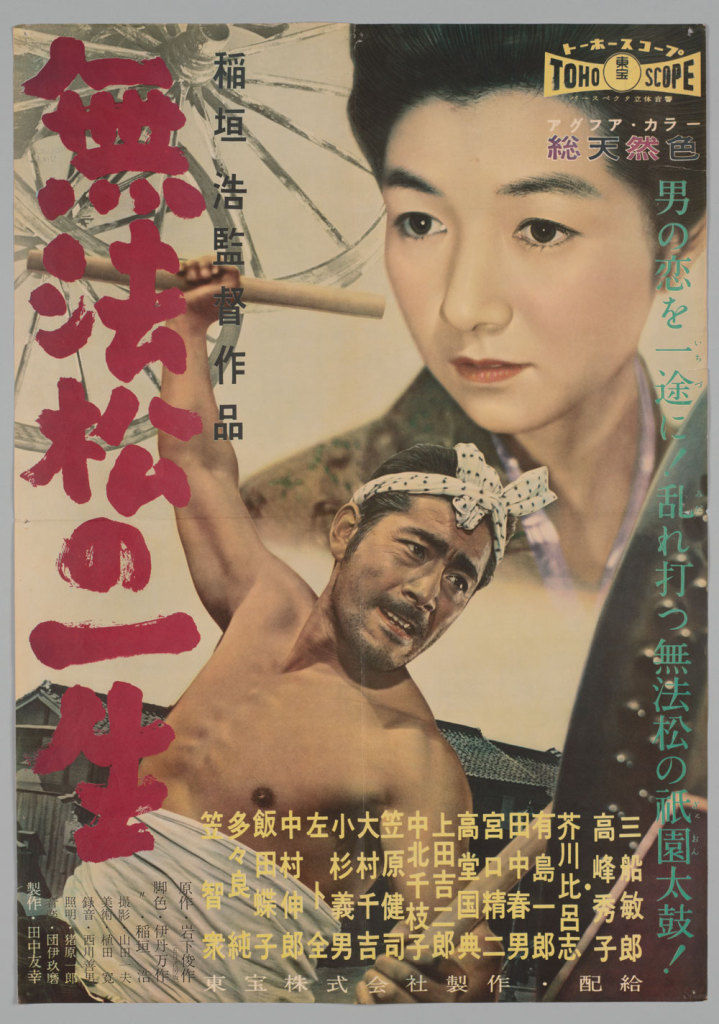

The movie screened at the La Brea’s “Gala Opening” was Muhōmatsu no isshō (1958; Fig. 1-05-025), a Tōhō feature directed by INAGAKI Hiroshi and starring MIFUNE Toshirō; Mifune even attended the show in person. Known more commonly as The Rickshaw Man, this remake of a 1943 production had garnered a Golden Lion prize at the Venice Film Festival of 1958. It’s just the sort of distinction, one imagines, that the art-house types who frequented the La Brea (formerly called the “Art La Brea Theatre”) would have been likely to appreciate. Promoters made much of Tōhō’s film-festival honors in their overseas publicity campaigns, although it was typically the studio’s dramas and not its special-effects movies that earned accolades of that sort. Argentinean (Fig. 1-05-026) and Yugoslavian (Fig. 1-05-027) posters for The Rickshaw Man both explicitly mention the Venice prize, the latter even supplying a gleaming image of the Golden Lion award near the bottom-right corner. A longer list of international film prizes won by Tōhō appears in an English-language catalog (Fig. 1-05-028) of 1963.

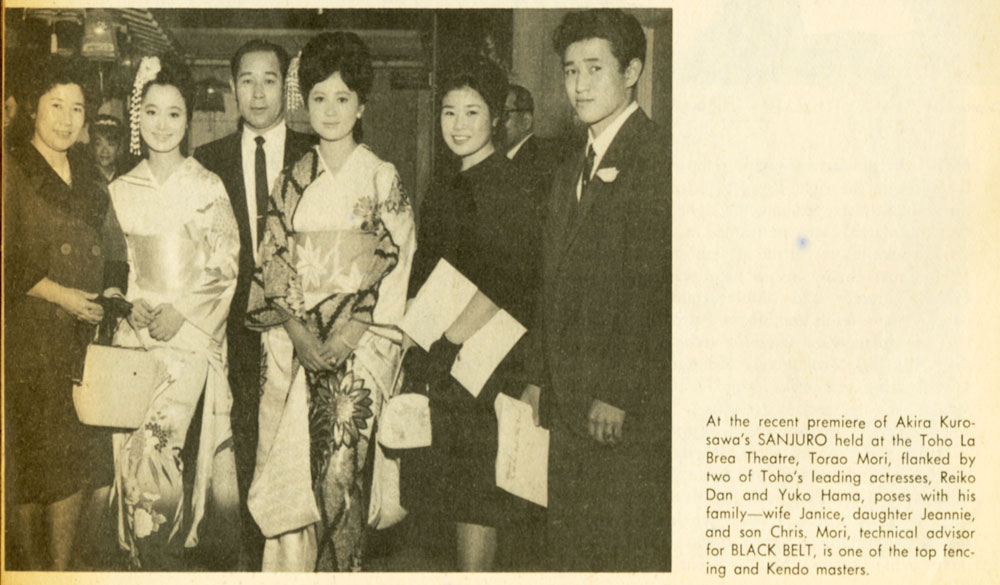

The Toho La Brea stayed in business until 1976, becoming, in the words of cinematographer John Bailey, a “necessary weekly stop for a generation of film students from USC and UCLA.” The theater’s stationery (Fig. 1-05-029) called it, more simply, a “HOME OF FIRST RUN JAPANESE FILMS.” The marquee of the La Brea may be glimpsed in the opening scene of The American Love Affair, a prizewinning 1976 documentary by Lee Rhoads, who was a USC film student at the time. It wasn’t just young filmmakers, though, who frequented the La Brea. According to a 1970 newspaper interview with basketball legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (still calling himself Lew Alcindor), who played varsity at UCLA from 1965 to 1969 as well as dabbling in the martial arts: “My favorite pastime was seeing the Samurai movies at the Toho Theatre on La Brea. I went there so often the people there thought I was a giant Japanese” (Long Beach Independent). A 1963 photograph (Fig. 1-05-030) in Black Belt—”The Magazine of Self-Defense”—similarly suggests an overlap between the theater’s audience and the local martial-arts community.

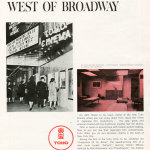

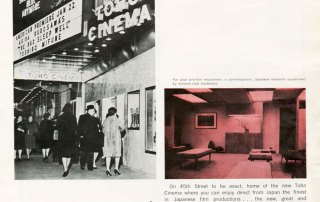

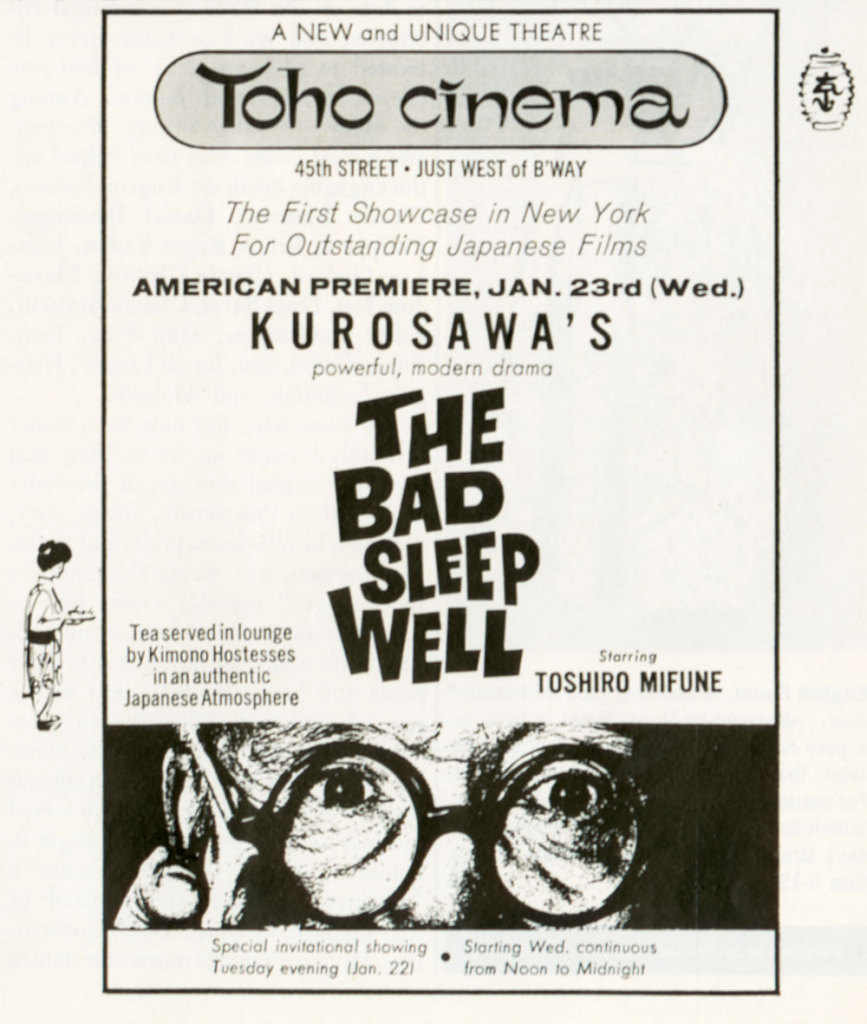

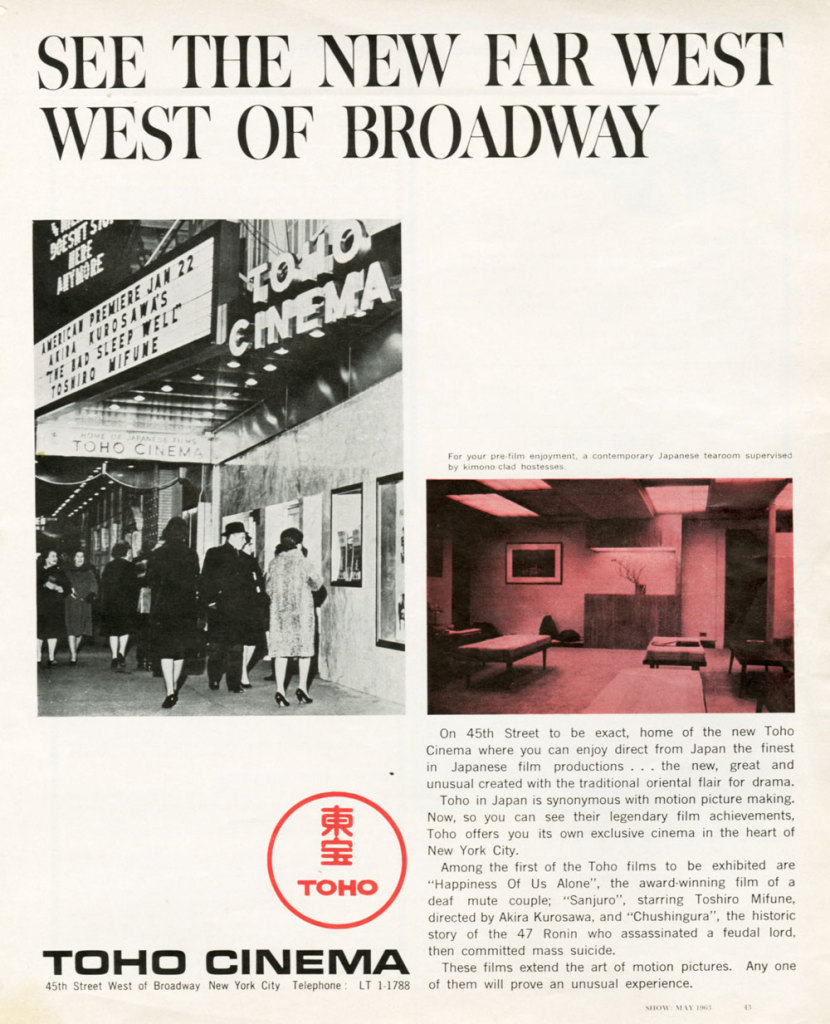

Meanwhile, on the East Coast, New York’s Toho Cinema greeted the public on January 22nd, 1963. The Toho, as it was called by in-the-know- Manhattanites, was located on 45th Street, just west of Broadway, a site presently occupied by a gigantic Marriott Hotel. A reincarnation of the historic Bijou Theater, which was built in 1917, the Toho, with 365 seats, stood not far from the much bigger Loew’s State on Times Square, where Godzilla, King of the Monsters! had premiered in 1956. An opening announcement (Fig. 1-05-031) in The New Yorker promised patrons “Tea served in lounge by Kimono Hostesses in an authentic Japanese Atmosphere.” A similar 1963 ad (Fig. 1-05-032) in Show magazine tints the same scene in suggestively pink hues, while also providing a view of the theater entrance.

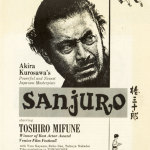

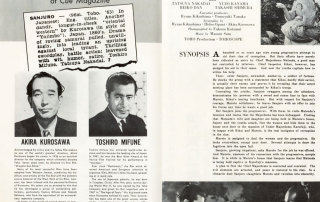

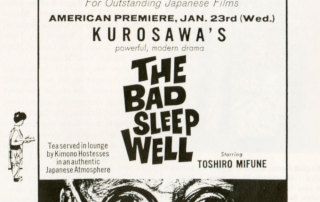

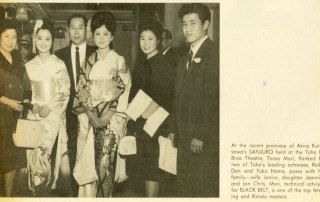

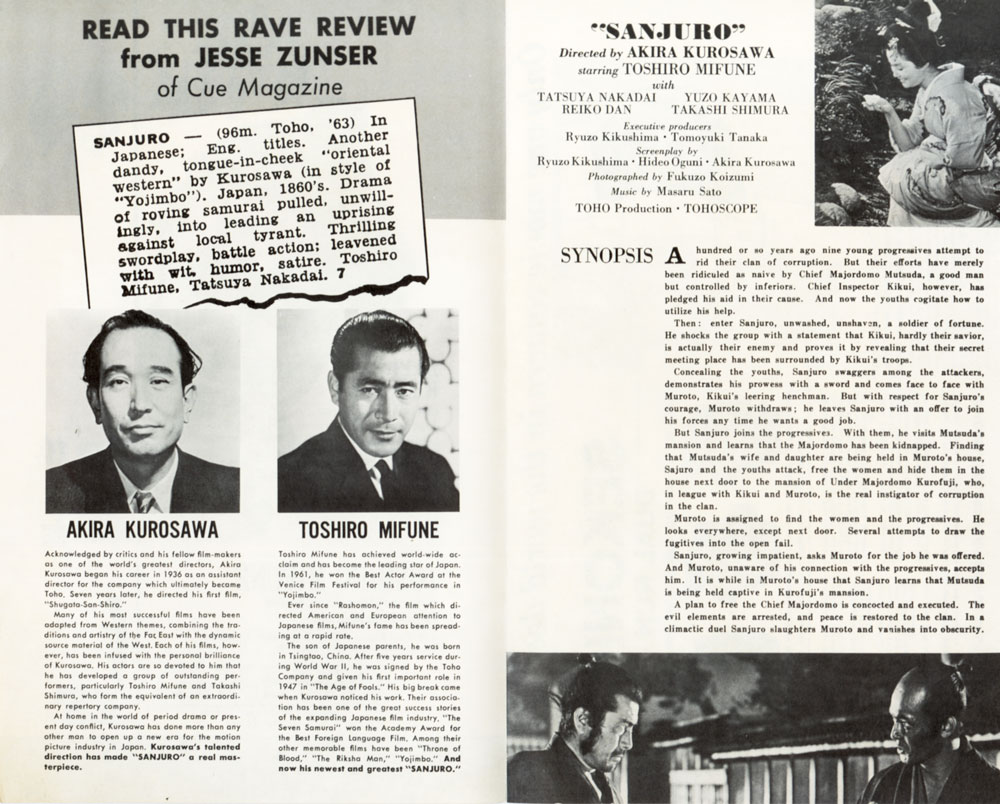

Not just feminine charms but also a bit of masculine swagger played a role in drawing visitors to the Toho, since, as in Los Angeles and Honolulu, the first movie shown was a vehicle for Japan’s most successful international star, MIFUNE Toshirō. As its opening feature the Toho screened The Bad Sleep Well (J. title: Warui yatsu hodo yoku nemuru; 1960), which, unlike many of the films that won Mifune acclaim overseas, was a contemporary drama rather than a period piece. Mifune headlined also in the samurai classic Sanjuro (J. title: Tsubaki Sanjūrō; 1962), which opened at the Toho in May 1963 (Fig. 1-05-033, Fig. 1-05-034). By the early Sixties, the director of both these films, KUROSAWA Akira, had, like Mifune, become well known to American cinemaphiles.

Manhattan’s Toho Cinema left less lasting a mark. After only two and a half years in business, it would close its doors in June 1965. By way of explanation, New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther (1905–1981) suggested that management “found the local interest in contemporary films from Japan too feeble and unreliable to warrant its going on.” The Tōhō company nevertheless continues to operate a New York office until the present day, located around the corner at 1501 Broadway.

In chronological order, San Francisco was the third U.S. city to receive a Tōhō cinema of its own (Honolulu was the fourth). The Toho Rio Theatre opened on 2240 Union Street in November 1963, taking over an Art Deco art house that had begun specializing in highbrow international productions in the Fifties, and which in 1959 had already hosted a Japanese film festival in collaboration with Tōhō. Described by one newspaper as “S. F.’s home away from home for Japanese films,” the Toho Rio stayed in business until June 1968. It was replaced in July 1971 by the Toho Theatre, at Post and Buchanan Streets in Japantown, next door to the recently completed Japan Center. Featuring a Japanese-style café or kissaten, the new movie house was built at a cost of $750,000. In the words of the San Mateo Times, programing at the Toho Theatre targeted “both Oriental and Caucasian audiences,” and focused on cultural documentaries during the daytime. In 1972 the cinema dissolved its formal affiliation with Tōhō and became the Kokusai Theatre, which continued to screen Japanese movies, of various studio origins, until 1987. The building now houses a Denny’s restaurant.

But Hollywood has never been the only picture in town. Already in the Sixties, the marquee of my local Pennsylvania theater reflected that diversity—and it was certainly no art house. If one were to drive into nearby Philadelphia, one might have found a venue or two that occasionally offered works by KUROSAWA Akira or other internationally acknowledged auteurs of Japanese cinema. But at the popcorn-bestrewn theaters that surrounded my neighborhood, those films weren’t likely to draw much of a crowd. Yet Japan made its presence felt all the same. In the form of what many locals simply referred to as the “Godzilla movie,” even the most parochial of Cold War suburbanites possessed a passing familiarity with the products of the Japanese film industry. Any picture that played, as in the case of my hometown, in an all-American, red-brick movie house flanked on one side by a soda fountain and on the other by a five-and-dime couldn’t be altogether foreign. Nor was Toho Company, Ltd., the studio that for all practical purposes invented the kaijū eiga, a purely Japanese operation. By the early Sixties, the Tokyo-based corporation ran four of its own theaters in the U.S.: the Toho La Brea Theatre in Los Angeles, the Toho Cinema in New York, the Toho Rio Theatre in San Francisco, and the Toho Theatre in Honolulu [VISUAL SIDEBAR 5: Tōhō and Toho]. Additional Tōhō offices could be found in Bangkok, Hong Kong, Jakarta, Lima, Manila, Naha (on the Japanese island of Okinawa, which U.S. occupation forces administered until 1972), Paris, Rome, and Saõ Paulo. If not everyone could travel to Japan to see the monsters, Japan’s kaijū were quite happy to come to them.

Which brings us to a second point about global monsters. The history of the kaijū eiga genre helps dispel any notion that globalization can be equated simply with the worldwide dissemination of things American, or even Western. Rather, globalization is a multidirectional process that has no single geographic center. It’s best imagined as creating a network of connections in which the point of origin is less pertinent than the path subsequently traveled. Godzilla and his fellow kaijū remind us that Japan-made cultural commodities began moving along those circuits long before the current Cool era. They successfully penetrated the global marketplace at a time when the Cold War system of cultural circulation was still in the process of coalescing. By way of historical background, it’s important to remember that the third quarter of the twentieth century saw a rapid acceleration of international trade and cultural exchange, following a prolonged disruption caused by the Second World War and the formation of regional economic blocs that preceded it. Under the Cold War order, America, the capitalist superpower, emerged as the so-called Free World’s biggest exporter of mass culture and of the collective fantasies it bred. Thus, as we all know, Baby Boomers in Western Europe, Latin America, the British Commonwealth, Japan, and elsewhere learned to love Lucy, desire Disney, and emulate Elvis simultaneously with their contemporaries in the United States.

It’s easy to forget, though, that in all these places children befriended not only Barbie, the American prom queen, but also Babar, the French elephant-king. A British Invasion occurred within the very framework of NATO, and had Cold War teens bouncing simultaneously to the Byrds and the Beatles. America never had a monopoly, in other words, on pop-culture exports. The integration of Japan into the economy of the Free World, which had been one of the goals of the Allied (but in fact American-dominated) Occupation of 1945–1952, brought that nation’s culture industries, too, into a globally expanding marketplace for mass entertainment. When American kids of the Sixties, myself included, plunked themselves down on suburban living-room floors to become engrossed in such TV shows as Astro Boy and Speed Racer, we were in fact viewing cartoons that had aired originally in Japan under the very different-sounding names of Tetsuwan atomu (1963–1966) and Mahha gō gō gō (1967–1968). The majority of us probably didn’t know that fact at the time, or were only marginally aware of it, since native English speakers had dubbed the voices, and East Asian physical features were less conspicuous in the case of animation (not yet called anime in the Sixties) than in live-action movies.

It’s difficult to say how our appreciation of these TV shows might have differed had we been more conscious of their creative origins in Japan. But marketers and distributors in the United States clearly worried that a too-evident Japaneseness would either distract our attention or dampen our enthusiasm. They made various efforts to conceal or at least tone down the visible and audible traces, changing titles and names into more American-sounding ones, dubbing voices, overlaying new theme music, and inserting lines that made the dialogue more culturally accessible to local viewers. Since the Fifties, those same techniques played a role in the overseas introduction of Godzilla and other Japanese film monsters. It was precisely this set of often slipshod conventions that Woody Allen satirized to hilarious effect in What’s Up, Tiger Lily?

The same repertory of “de-Japanizing” techniques survives to some extent today, even in an era when anime from Japan abounds on American television. Nowadays, though, there’s a significant difference. A growing community of young consumers prizes and deliberately seeks out Japaneseness, regarding it as more or less synonymous with Coolness. Traces of Japanese origin are no longer so assiduously erased from made-in-Japan products. American youngsters now routinely encounter (and by some accounts are increasingly able to recognize, if not necessarily to pronounce) Japanese written characters on their videogame and television screens. And one doesn’t have to have seen much cartoon programming recently made in the U.S. to realize how deeply it borrows from Japanese anime.

A third factor that makes kaijū eiga valuable for learning about globalization relates to the genre’s origins in East Asia. For historical reasons, a greater cultural and linguistic distance separates Japan from the majority of producers and consumers of commodities for the global marketplace than the boundaries that divide the various Euro-American societies that have dominated the global mass-entertainment industry until recently. Therefore, the work of accommodating Japanese cultural goods to the overseas markets in which they will be consumed often involves more steps and more artifice than were required, say, to make the Beatles—no matter how lovably Liverpudlian—accessible to American teenagers of the Sixties. For one thing, the Beatles spoke English. It was Yoko Ono whom Americans had a harder time understanding.

Cultural adaptation involves more than language alone. Among software manufacturers, the term globalization has come to refer to the deliberate tailoring of products for diverse and discrete groups of consumers abroad. Over the years, a number of companies have become quite skilled at developing merchandise that crosses not only national boundaries but also significant cultural barriers. Nintendo’s Pokémon cards, for example, still enthusiastically collected by many children around the world, feature different names for the depicted “pocket monsters” when they are sold in the United States and other English-speaking countries than when they are initially released on the domestic Japanese market. The Kyoto-based corporation, along with its overseas subsidiaries, has developed French and German nomenclatures as well. The varying designations take into account not only language differences but also native cultural traditions, including local monster lore. Thus, the vampire bat–like Pokémon who in the U.S. goes by the name of Golbat—shortened, apparently, from Golden Bat—is better known in France as Nosferalto. (Nosferatu was the title of one of the earliest film versions of Dracula.) Following the same principle, kids in English-speaking countries call the Pokémon sea-serpent Kairyū by the name Dragonite, while in France he is Dracolosse. And so forth. Nintendo’s multilingual and multicultural business strategy, though skillfully executed, is by no means new. In fact it has precedents in the various techniques that emerged, largely through trial and error, as kaijū eiga makers and distributors marketed their own monster commodities during the early decades of the Cold War era.

The steady proliferation of monster names helps illustrate a fourth lesson of kaijū eiga. Although many critics equate globalization with cultural homogenization, the two aren’t synonymous. My interpretation draws on the work of cultural anthropologist Arjun Apparudai, who encourages us to view the global and the local as intertwined aspects of the same process. Goods may circulate globally, but in the end they can only be consumed locally, that is to say, in a particular place. Their meaning and value is deeply affected by cultural and historical conditions that are specific to that geographic setting. Therefore, a single product can acquire a variety of identities and uses depending on where on the globe it is to be found. What may seem at first sight a growing sameness of culture around the world may entail, from a different vantage point, the creation of new forms of diversity. Some commentators have dubbed this process of cultural adaptation glocalization, using a term that reportedly originated in the Japanese corporate world during the Eighties. Godzilla and his progeny offer a concrete and detailed example of that phenomenon at work across space and over time. This website attempts to map the cultural history of globalization (or, if you prefer, glocalization) by exploring the multiple and varied guises that Godzilla assumed in his travels around the world, together with fellow kaijū, between the Fifties and the Seventies. In doing so, it offers an early glimpse of some of the forces that powerfully shape our lives and consciousness today.

My fifth and final point has to do with the particular subject matter of the global products considered here, namely that creature we call the monster. Long before people started talking about “globalization,” monsters, or at least their representations, could be found in any society. Given monsters’ ubiquity, you’d hardly think they needed export. Nor does classical economic theory encourage us to look at such things as fantasy and fear as exportable substances. But that’s exactly what they’ve become in modern mass societies, as much a part of global trade as soybeans and silicon. The cinema medium provides a powerful vehicle for conveying these intangible commodities, creating an intimate experience out of materials and images that may have traveled great distances to reach their end-users. And because, particularly in the case of kaijū eiga and other fantasy genres, the experience of film takes place as much at the unconscious as at the conscious level, movie monsters like Godzilla, or, for that matter, Dracula or Frankenstein—none of whom were originally U.S. citizens, it might be noted—bridge the global and the local in a peculiarly personal way.

A course I’ve been offering at Columbia University for a number of years on the cultural history of monsters has taught me to recognize an important paradox. Although most of us are accustomed to thinking of monsters as hell-bent on destroying human civilization, they are more effective, by far, as community builders. As a fellow Japan historian, Gerald Figal, once put it, “Monsters could do without civilization, but civilization could not do without monsters.” An emerging body of literature, dubbed “monster theory” by Jeffrey Cohen, a pioneer of the field, offers insights into this paradox. It maintains that, in different times and places, monsters have fulfilled a crucial cultural role in symbolizing and in conveying the core values of the people who believe in them, if only by embodying the antitheses of those communally sanctioned principles. No matter how conditional and temporary our belief in monsters may be, the shared knowledge of them helps to define the collective imagination of assorted readers, listeners, and viewers. On one level, monsters seem scary because they remind us that we are vulnerable to forces beyond our control. At the same time, by confronting us with imaginary dangers, they help construct consensus out of chaos and make us aware of common ideals and responsibilities. The same principle holds true whether the community in which ideas about monsters circulate is a regional culture or a national populace or the broader market of consumers that multinational corporations nowadays serve. How the nature of this kind of collective consciousness has changed over time as mass-produced images of monsters, and especially those called kaijū, have circulated throughout the world is one of the stories that this website records.