CONTINUED FROM MODULE 2 PART 1

UNLUCKY DRAGON

Which brings us to another of Godzilla’s multiple beginnings. One of Gojira‘s notable features is the fact the movie offers not just one possible origin for the creature, but two. The film scholar Vivian Sobchack, in her 1987 book Screening Space, has usefully defined science-fiction cinema as a genre that “emphasizes actual, extrapolative, or speculative science and the empirical method, interacting in a social context with the lesser, but still present, transcendentalism of magic and religion.” True to form, in the case of Gojira, a more scientific explanation of the monster’s existence competes with, and ultimately supersedes, the magico-religious one introduced at the story’s beginning. Whereas the islanders of Ōdo conceive of Godzilla as a mythic, semi-divine creature, a scientific team that visits the island early in the film identifies him instead as a giant dinosaur, a zoological survivor from a transitional period between the Jurassic and Cretaceous eras. They lay the blame for his recent rampages and apparent radioactivity on having been exposed to and, presumably, transformed by hydrogen-bomb tests that U.S. military authorities are conducting in the northwest Pacific. The “scientific” explanation of Godzilla, then, like its magico-religious counterpart, highlights the trans-Pacific connections that underlie the film’s making.

The H-bomb testing referred to in the movie isn’t film fantasy but historical fact. Following Japan’s defeat in World War Two, the United States assumed control of the enemy’s former island territories in Micronesia, or what wartime Japanese had called the “South Seas.” There, U.S. scientists and military planners continued development of the nuclear-weapons program that had helped bring about, or at least made inevitable, Japan’s surrender. Indigenous islanders were moved off their peaceful atolls to “protect” them from the engineered blasts and ensuing fallout, and some were never able to return. These days, the word bikini denotes little more than a type of swimwear. But for the early postwar generation it evoked images of earth-shattering power. Between 1946 and 1958, itsy-bitsy Bikini Atoll was the site of more than twenty nuclear tests, including the so-called Bravo Shot, part of Operation Castle, which still ranks as the second most powerful nuclear detonation in history and the largest ever set off by the United States.

Figure 2-03-001

These days, the Lucky Dragon No. 5 (Daigo fukuryū maru) probably doesn’t ring a bell for the average person in Japan, much less in the United States. The deceptively quaint name belongs to a Japanese commercial fishing boat that, in March 1954, was accidentally irradiated by a U.S. hydrogen-bomb test while trawling for tuna near Bikini (or Pikinni) Atoll in what were then the American-governed Marshall Islands. The thirty-meter-long vessel (Fig. 02-03-001) sits today in a specially designed exhibition hall near Tokyo Harbor, visited by busloads of schoolchildren, adult tourists, and curiosity seekers.

In the cinematic realm, the craft has cast an even longer shadow. Around the world, movie audiences of the Cold War period encountered various incarnations of the Lucky Dragon, each in its own way presenting a disquieting reminder of the dangers of nuclear-weapons testing, no matter if it was sea- or land-based.

In the case of Tōhō, a ship modeled after the Lucky Dragon plays an important role in not one but two of the studio’s film classics of the Fifties. One of those vessels appears in the opening scene of Gojira and goes by the name of Glory No. 5 (Daigo eikō maru). Audiences witness the crewmen relaxing peacefully on deck, when suddenly a blinding flash of light bursts forth, followed by a powerful gust of wind. Both phenomena are classic aftereffects of a nuclear explosion. In the case of Gojira, however, viewers learn eventually that the source of the disturbance is a radioactive monster, namely Godzilla himself.

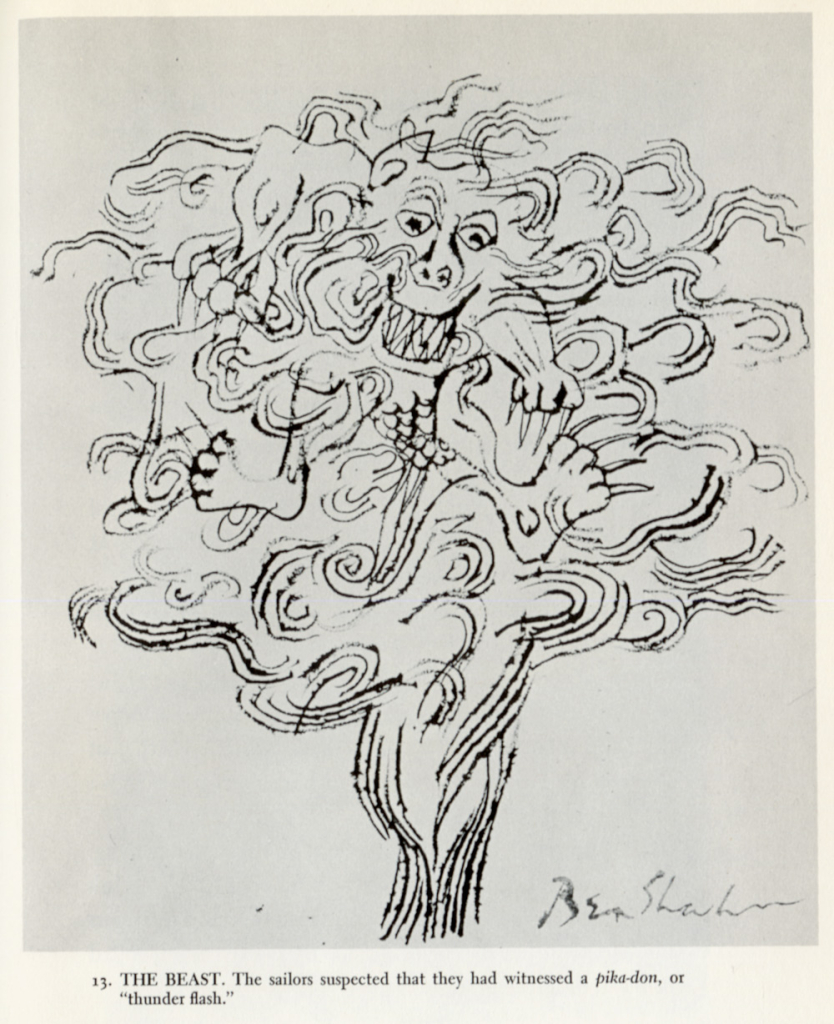

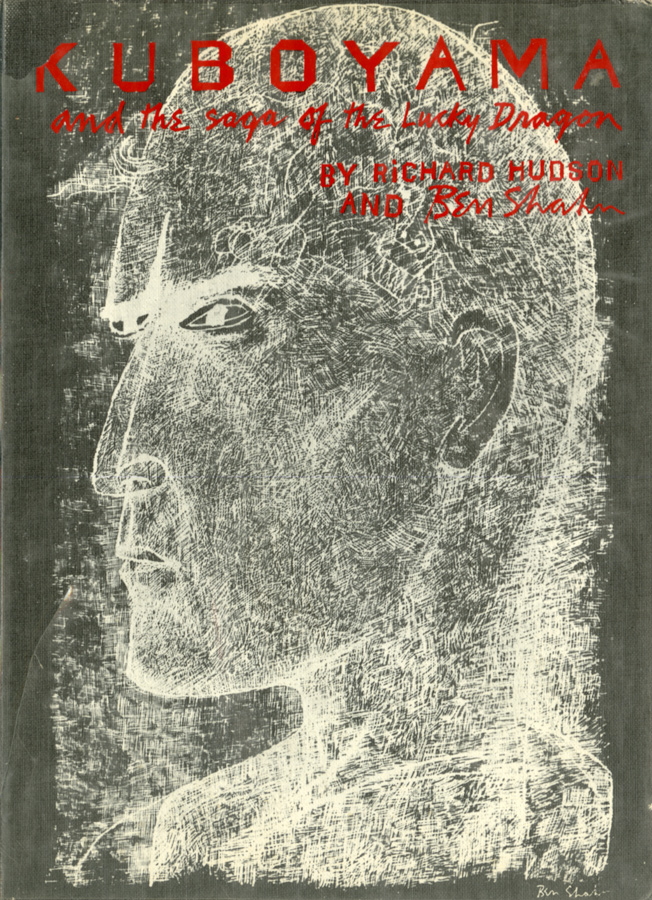

It’s historically poignant that only the Japanese language possesses a colloquial expression—pika—for the peculiar kind of light that’s generated by an atomic blast, or pikadon, if you remain alive to hear the subsequent boom. The American social-realist painter Ben Shahn (1898–1969) endowed the ominous “thunder flash” with metaphorical scales and teeth in a 1957 work in ink he titled “The Beast” (Fig. 2-03-002). Shahn’s sketch, along with others like it, would furnish the illustrations for a 1965 picture book called Kuboyama and the Saga of the Lucky Dragon (Fig. 2-03-003), which the artist published together with writer Richard Hudson for the purpose of antinuclear education.

Four years after the Lucky Dragon incident, a disturbingly irradiated ship would appear again in a special-effects feature from Tōhō, namely The H-Man (1958). The stricken craft emerges in an extended flashback sequence, adrift in the nighttime ocean. A U.S. lobby card (Fig. 2-03-004) for the movie shows the seemingly deserted trawler, dubbed Dragon God No. 2 (Daini ryūjin maru), as a group of fishermen from another vessel climb aboard to make an inspection. Shortly afterwards, the boarding party, as well as the movie audience, discover that the Dragon God‘s crew has been liquefied. The H-Man‘s plot can be understood, at least on one level, as an Atomic Age recycling of older Japanese folktales about “ship ghosts,” or funayūrei. Such spirits were traditionally believed to appear on or near seagoing vessels and to represent the souls of drowned seafarers. For an early nineteenth-century depiction of that maritime menace, see this module’s Figure 2-10-007.

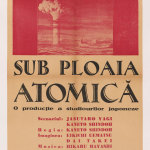

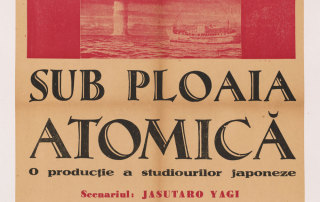

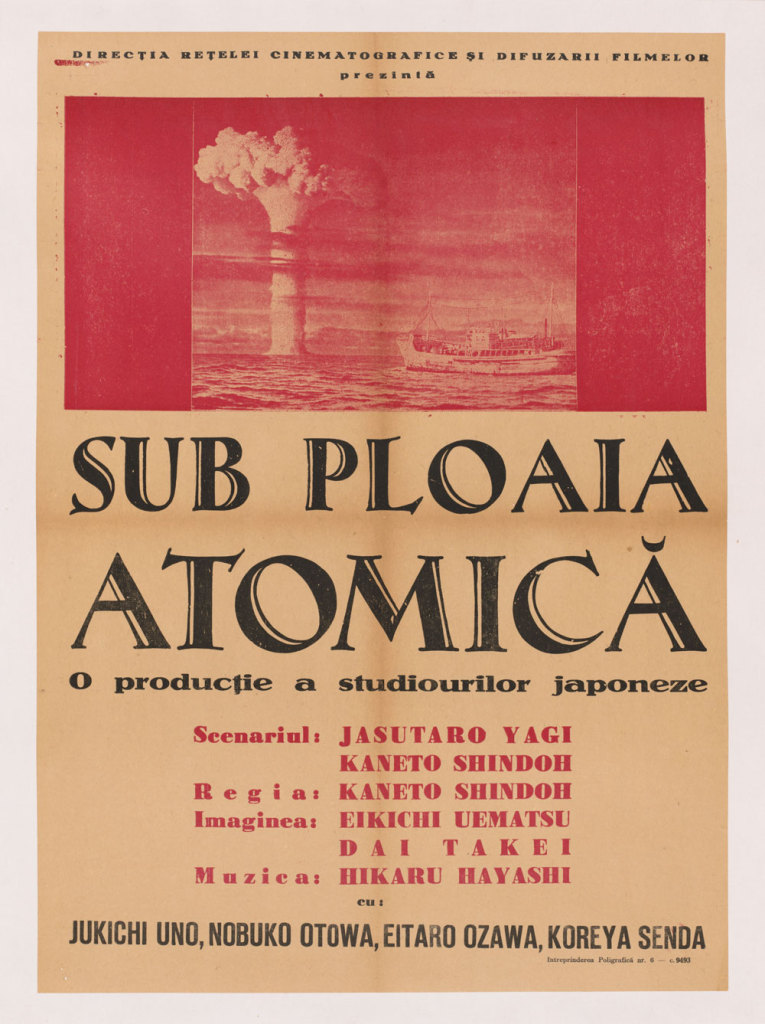

Yugoslavian (Fig. 2-03-005) and Romanian (Fig. 2-03-006) posters advertise yet another made-in-Japan retelling of the Lucky Dragon incident. Directed by Hiroshima native SHINDŌ Kaneto (1912–2012), this third movie took the form of a docudrama rather than a fiction film, and simply used the name of the ship—Daigo fukuryū maru—for its title. Although Daigo fukuryū maru, like most of Shindō’s works, was an independent production, it was commercially released by Daiei, one of Japan’s largest studios. Daigo fukuryū maru focuses on the tragic experience of KUBOYAMA Aikichi (1914–1954), who worked as a radio operator on the real-life trawler and became the period’s most famous radiation victim—at least of the nonfictional kind. The same Kuboyama appears as the main figure in, and is depicted on the front cover of, Shahn and Hilton’s illustrated storybook of 1965, Kuboyama and the Saga of the Lucky Dragon, shown above.

Figure 2-03-007

Playing the part of a U.S. Navy medical officer in Daigo fukuryū maru—or as the film was titled in Romanian, “Beneath the Atomic Rain”—was Harold Conway (1911–1996). More an amateur than a professional, Conway was an American actor who worked and eventually passed away in Japan. His bespectacled face can be spotted in the Yugoslavian poster above all the other faces along the left edge of the image, next to the Serbo-Croatian title, Smrt na Pacificu (Death in the Pacific). Hardcore fans of kaijū eiga and tokusatsu eiga have probably seen Conway’s face before, although they may not immediately recognize it. When Japanese studios of the early Cold War period needed a Caucasian male to play the part of a foreign diplomat, scientist, journalist, minister, or military officer—and especially when that part required some ability to speak Japanese, however accented—Conway was one of the people whom they regularly called. That’s Conway hamming it up, for example, third from the right on a U.S. publicity still (Fig. 2-03-007) for King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), a movie, like Daigo fukuryū maru, in which he plays a scientist. Other made-in-Japan monster and sci-fi movies that Conway appeared in during the Fifties and Sixties include The Mysterians, Battle in Outer Space, Invasion of the Neptune Men, Mothra, The Last War, Mothra vs. Godzilla, and Genocide.

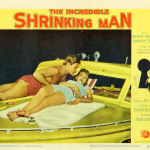

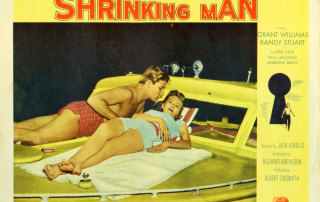

Outside Japan, too, Cold War filmmakers loaded nuclear anxieties aboard cinematic vessels of various kinds. The ripples of the Lucky Dragon incident can easily be detected, for example, in Universal’s sci-fi classic The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), adapted by Richard Matheson from his own novel of the previous year. At the time of the real-life Lucky Dragon incident in 1954, the ship’s crew had found itself blanketed by a layer of radioactive ash—consisting mainly of pulverized bits of coral reef—while fishing about 130 kilometers from Bikini Atoll. The title character of 1957’s Incredible Shrinking Man, on the other hand, passes through a “weird mist” while he’s relaxing aboard a motorboat somewhere inside the borders of the United States (Fig. 2-03-008, Fig. 2-03-009, Fig. 2-03-010). It’s this puzzling precipitation, together with the character’s previous exposure to some sort of pesticide—another revealing emblem of the widespread mid-twentieth-century faith and simultaneous mistrust in science—that’s responsible, allegedly, for his irradiation and subsequently diminished physical stature.

Figure 2-03-11

Meanwhile, Port of Hell, an Allied Artists picture of 1954, envisioned the prospect of a nuke being smuggled aboard a commercial freighter. Although the movie narrative involves a Soviet plot to infiltrate the United States, the offshore mushroom cloud and incapacitated vessels of the American half-sheet poster (Fig. 2-03-011) could easily have suggested to a casual viewer a more Bikini-like set of circumstances—especially given the film’s release just nine months after the Lucky Dragon affair. For the American public, whom Cold War photojournalism exposed repeatedly to images of Pacific weapons testing, sometimes involving the sinking of demobilized warships and other vessels for experimental purposes, seaborne scenarios of atomic peril held no less power to unsettle the psyche than scenes of terrestrial devastation.

Even in Japan, where the effects of Hiroshima and Nagasaki remained all too visible on dry land, a child’s playing card or menko (Fig. 2-03-012) from the Bikini era depicts the “atomic bomb” (genshi bakudan) in an oceanic setting, complete with a sinking vessel. The view is essentially the same on a U.S. trading card (Fig. 2-03-013) from 1954, which recreates the scene of the very first “BIKINI A-BOMB TEST” on June 30th, 1946, part of a Topps series featuring classic newspaper headlines.

The Bravo Shot of March 1st, 1954, involved a hydrogen bomb rather than a conventional atomic weapon. The device’s yield proved even greater than planners had anticipated, no less than one thousand times more destructive than the A-bomb that devastated Hiroshima. Fallout from the blast spread far outside the official exclusion zone that U.S. authorities had established around Bikini, with disastrous consequences. Indigenous Marshall Islanders on the neighboring atolls suffered high doses of radiation, as did the crew of a hapless Japanese tuna trawler, ironically named the Lucky Dragon No. 5 (Daigo fukuryū maru) [VISUAL SIDEBAR 3: Requiem for a Dragon]. The ship’s chief radio operator, forty-year-old KUBOYAMA Aikichi, died of complications six months later, reputedly the first human victim of the H-bomb.

One of the origins of Gojira the film, and not just Godzilla the monster, lies in this real-world episode. The tragedy of the Lucky Dragon, and the risks of consuming irradiated “atomic tuna” (genshi maguro) were on the lips of many Japanese during the spring of 1954. Around the same time, the Tōhō studio producer TANAKA Tomoyuki (also known as TANAKA Yūkō; 1910–1997) was searching for a theme for his next motion picture, an earlier scheduled project having just fallen through. To Tanaka’s way of thinking, a movie dramatizing the dangers of nuclear-weapons testing stood to gain from the ongoing controversy surrounding the Bravo Shot, which would in effect serve as pre-publicity. Shooting began that summer [VISUAL SIDEBAR 4: Girls with Pearls] and the resulting film, Gojira, premiered in Tokyo, to sellout crowds, on November 3rd, 1954. The date is significant, since the 3rd of November—birthday of Hirohito’s grandfather, the emperor Meiji—had come to be celebrated in postwar Japan as “Culture Day,” and even today draws big audiences to movie houses.

Another one of Godzilla’s many birthplaces lies on the Pacific coast of Japan’s main island, Honshu, in the Ise-Shima region. It was in the coastal town of Ijika (part of today’s Toba City) that, in or around August 1954, the crew of Gojira filmed those scenes that supposedly take place on Ōdo Island. Gojira‘s director, HONDA Ishirō, was well acquainted with the Ise-Shima area, since he’d directed his first feature-length movie there in 1951. That earlier picture, Aoi shinju (Blue pearl), revolved around the region’s celebrated female pearl divers, although it’s far less well remembered today than Gojira.

The choice of shooting location helps explain why Gojira holds the dubious distinction of being the only classic sci-fi film of the Fifties to display naked female breasts. As late as the Sixties, local pearl divers in Ise-Shima reputedly swam only in loincloths. Three or four such female divers, known as ama, appear topless in one of Gojira‘s early scenes, if only for a few seconds. Presumably natives of Ijika, they stand on the beach with fellow “Ōdo Islanders,” scanning the horizon for possible castaways. Most likely, Honda incorporated the women into the shot in order to enhance the film’s local color and to underscore the message that Ōdo Island—rather like King Kong‘s “Skull Island”—lies far removed from modern industrial society, with its distinctive notions of propriety. Additionally, of course, there’s the titillation factor. I hope it’s not too uncharitable to note that the women are long in the tooth, perhaps diving-industry veterans.

Figure 2-04-001

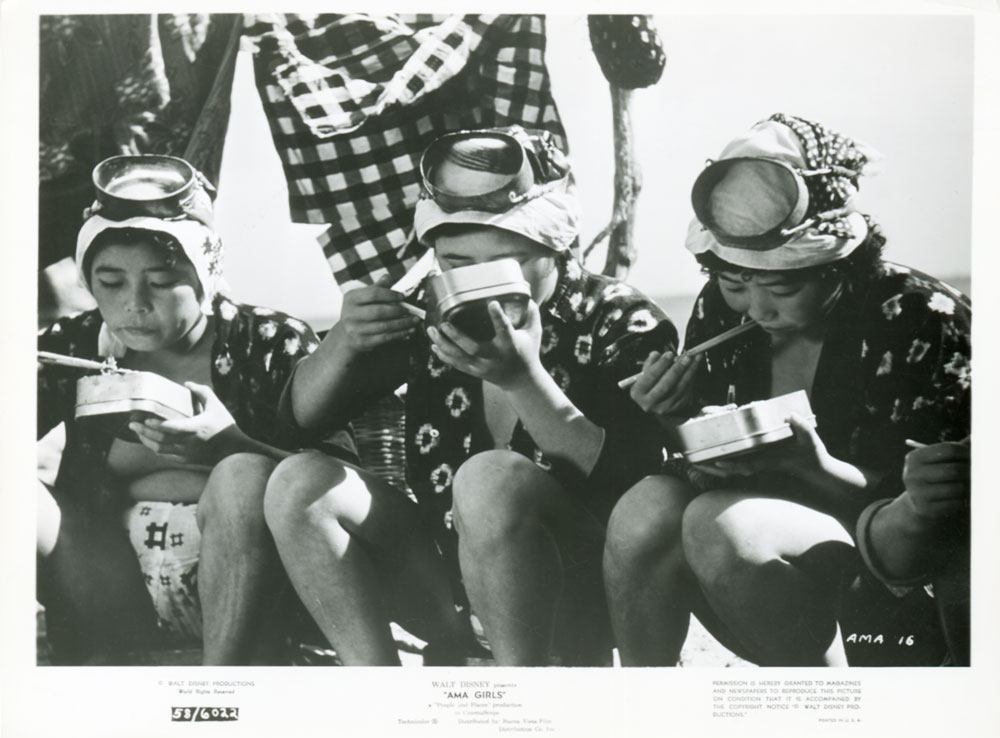

On the other side of the Pacific, Hollywood editors left exposed breasts intact when they converted Gojira into a more American-friendly feature in 1956. This was despite the fact that, elsewhere in the film, they’d trimmed away many minutes of original footage. It’s hard to imagine American popular as well as legal mores of the Fifties allowing such a revealing display of female flesh had the movie been set domestically in the U.S. The relatively relaxed attitude exemplifies what might be called a National Geographic approach to nudity—in other words, the idea that nakedness is “cultural” and therefore not obscene when viewed in the context of supposedly more backward, non-Western societies. Even Disney studios, that champion of American wholesomeness, couldn’t resist plunging into the business of ama spectacle, releasing a short documentary called Ama Girls in 1958. Is it just my imagination, or is that a nipple peeking out from beneath one of the pearl divers’ swimming attire in one of Disney’s publicity stills (Fig. 2-04-001)?

Figure 2-04-002

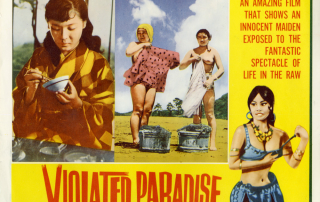

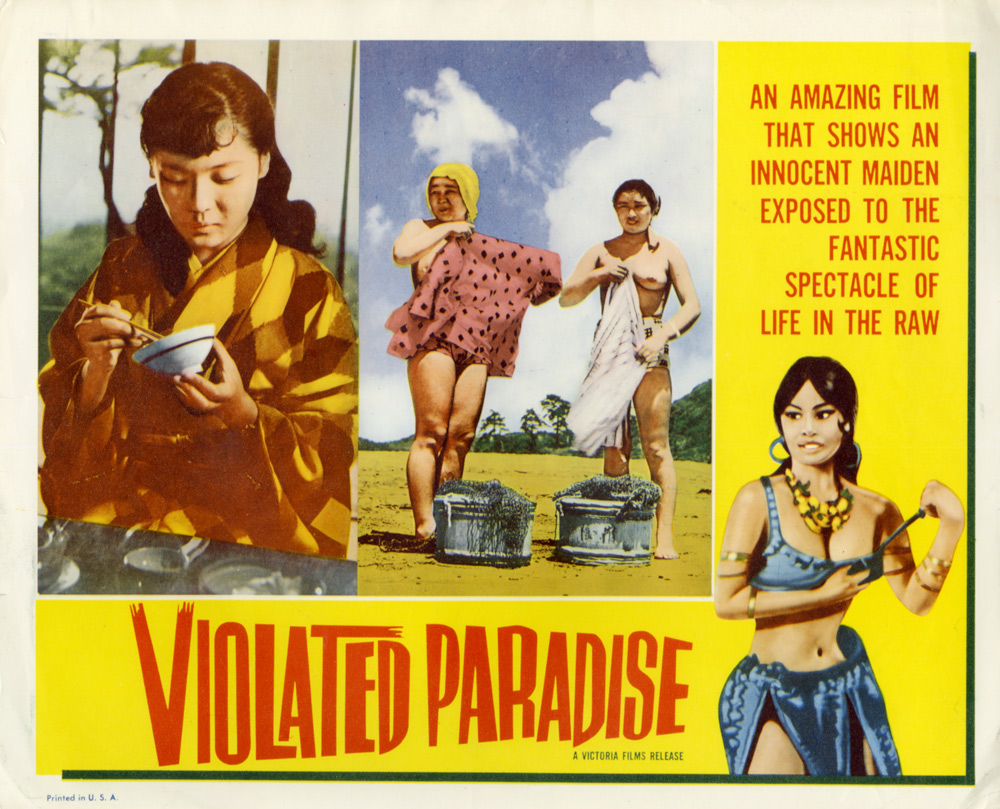

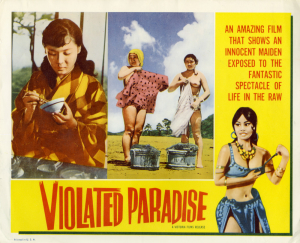

The same sort of expedient cultural distancing permitted some remarkably risqué fare from Japan to be screened at American cinemas and drive-ins of the late Fifties and early Sixties. Among the Japan-related exotica was a pseudo-documentary sexploitation flick known as Violated Paradise (1963), or alternatively as Diving Girls of Japan, AKA Scintillating Sin, AKA Sea Nymphs (Fig. 2-04-002). Publicity material for Violated Paradise went so far as to proclaim that, “In Japan there is no shame in nakedness.” Despite the provocative title, Violated Paradise drew a considerable portion of its footage from the camera of the respected Italian photographer-ethnographer Fosco Maraini (1912–2004). Capitalist commerce and cultural anthropology make for perfectly comfortable bedfellows, especially in the cinematic realm.

Figure 2-04-003

Shame-free or not, mainstream actresses rarely exposed their breasts in Japanese cinema up until right around the time of Godzilla’s birth. In 1956, an uncommonly buxom Japanese starlet named MAEDA Michiko (born 1934) caused a domestic sensation by stripping to the skin in Onna shinjuō no fukushū (Revenge of the pearl queen), a Shintōhō (“New Tōhō”) suspense picture with a pearl-diving locale. The pearl-diver formula proved such a convenient pretext for baring female flesh that the same studio, which had split from Tōhō over labor issues in 1947, decided to star Maeda in another ama-drama (Ama no senritsu [The pearl diver’s terror]) the following year. Both movies were no doubt too racy to be shown in mainstream American theaters. But Onna shinjuō no fukushū, the earlier of the two, passed muster in West Germany, a place where viewers tended on the whole to be less prudish than their Yankee counterparts. As seen on the 1958 German poster (Fig. 2-04-003), it played in that country under the title “Island of Hard-Hearted Men.”

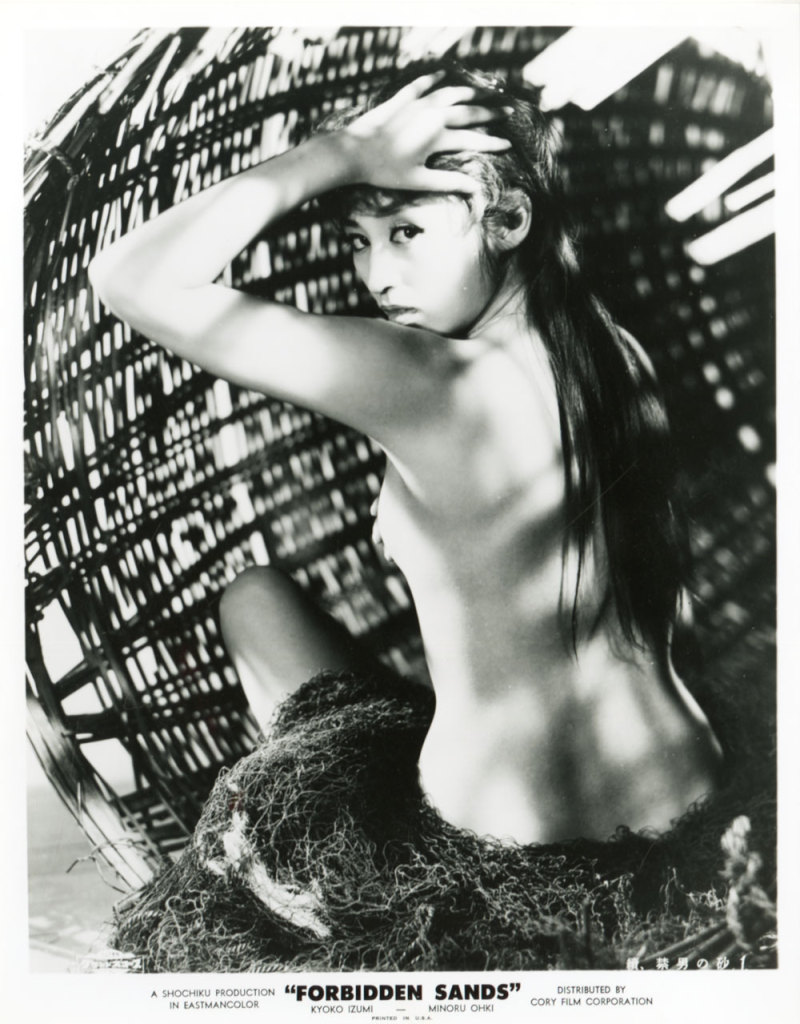

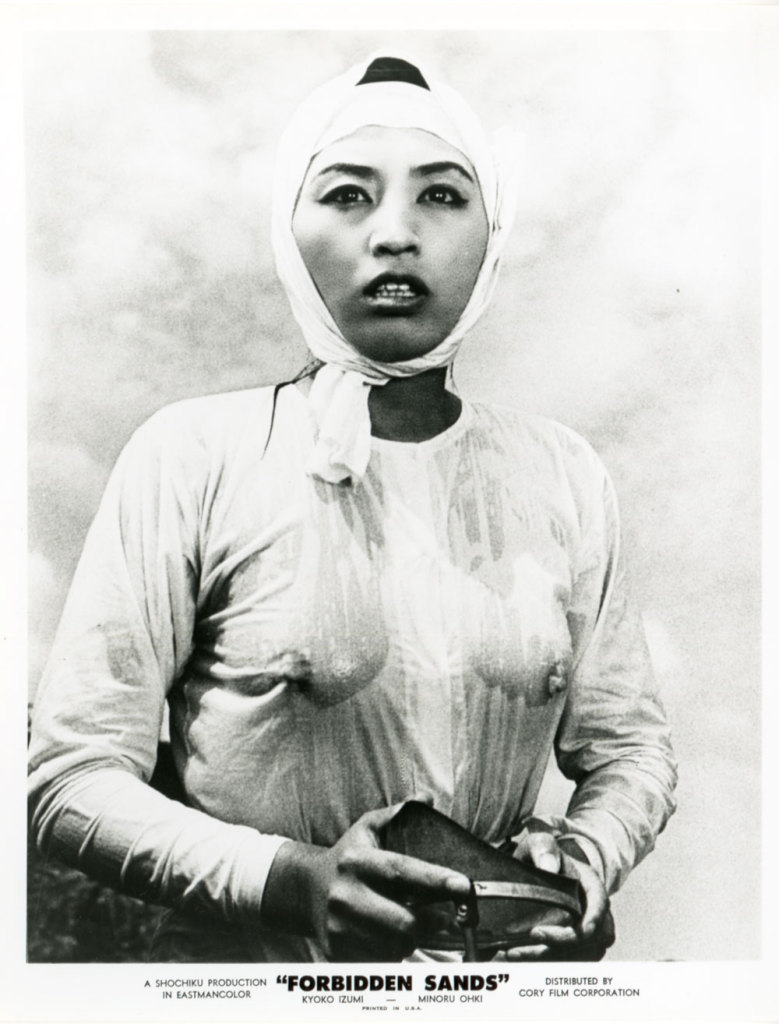

One ama-drama that made it to America, if not necessarily to Main Street movie houses, was Forbidden Sands (Japanese title: Kindan no suna), a 1958 Shōchiku production that debuted on the U.S. adult-theater circuit in 1960. The film’s Stateside distributor was Cory Film Corporation, a smaller Hollywood outfit that would also have a hand in the 1962 transformation of Tōhō’s Daikaijū Baran into Varan the Unbelievable. The steamy publicity stills (Fig. 2-04-004, Fig. 2-04-005, Fig. 2-04-006) that Cory Film issued to promote Forbidden Sands‘ release clearly suggest that it was aiming for more than just an anthropological viewership. In 1964, Forbidden Sands could still be seen at the Strand Art Theatre (which remains in existence today) in Kansas City, Missouri, paired with a 1962 Hollywood swimfest called Bachelor Tom and His Bikini Playmates (Fig. 2-04-007).

As if Godzilla’s geographic origins weren’t complicated enough, there’s one more odd wrinkle to his birth story. When Hollywood producers Americanized Gojira in 1956, they shot additional scenes of “Ōdo Island” at a Los Angeles studio and incorporated that footage into the U.S. version of the movie (King of the Monsters). Those scenes form part of a longer sequence (Fig. 2-04-008) showing islanders—accompanied, in the American reshoot, by Raymond Burr—as they flee down a mountainside. The Hollywood crew attempted as best it could to match the costumes of Ōdo (which is to say, Ijika) residents, but certain details give away the American origins of the newly inserted footage and cast. For example, one of the male extras who appears in the Stateside version wears a happi coat that’s emblazoned with Japanese (katakana) lettering reading “Lucille Anderson.” It’s possibly a monogrammed souvenir from someone’s visit to Japan, or perhaps to Little Tokyo.

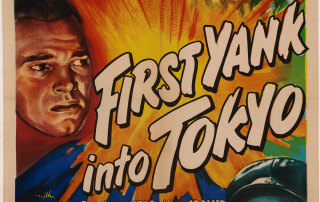

Remarkably, what looks like the very same happi coat can be seen in RKO’s 1945 war drama First Yank in Tokyo. The garment is worn there by Keye Luke (1904–1991)—second from the left on the U.S. lobby card (Fig. 2-04-009)—who plays the part of a Korean male helping the “Yank” undercover agent slip behind Japanese enemy lines during World War Two in order to rescue an American atomic scientist. You can make out the “Lucille Anderson” monogram quite clearly in one of the U.S. publicity stills (Fig. 2-04-010) for First Yank in Tokyo, although the designer of the corresponding one-sheet poster (Fig. 2-04-011) abstracts the lettering nearly to the point of illegibility. In 1959, Keye Luke would go on to voice some of the English-language dialogue for Gigantis the Fire Monster, a dubbed version of the second Godzilla movie.

The decision to make Gojira was not just a canny commercial stratagem. It was certainly that as well, but it was also a political statement that echoed and informed public views. This political message emerges most explicitly in the original story treatment that Tanaka commissioned from KAYAMA Shigeru (1904–1975), a former treasury official who became one of Japan’s most notable mystery and science-fiction writers of the early postwar era. Kayama began his treatment with the following narration: “1952, November [1st]… on this day our earth was scarred by a terrifying experiment the likes of which no one could ever have conceived—the first hydrogen-bomb experiment.” That voice-over, however, didn’t make it into the final version of the script, because HONDA Ishirō (1911–1993) and MURATA Takeo (1910–1994), cowriters of the screenplay, wanted to keep Godzilla’s initial appearance a mystery for the audience. Similarly scrapped was Kayama’s original ending. His story treatment envisaged the president of the United States, having learned of the devastation that Godzilla has caused in Tokyo, declaring a halt to his nation’s thermonuclear tests in the Pacific. A parallel pronouncement was supposed to issue from the Soviet Union, which had exploded its first H-bomb in 1953, a year prior to Gojira‘s release. Interestingly, Kayama originally placed Ōdo not in the Pacific Ocean, but in the Sea of Japan (Korea’s “Eastern Sea”) to the northwest of the Japanese archipelago. That location would have made it roughly equidistant from Soviet and American-controlled territories, possibly an attempt on Kayama’s part to balance the Cold War blame.

Needless to say, the U.S. didn’t cut short its nuclear-weapons program. In fact, it continued testing hydrogen bombs in the Pacific Ocean until 1962. However, the public outcry that arose from the Lucky Dragon incident, and that Gojira‘s success helped keep in the spotlight, had repercussions far beyond the film industry. Women’s groups in Japan spearheaded a petition campaign to ban the Bomb that ultimately gathered signatures from more than a third of the country’s population. A scene early in Gojira in which a group of female parliamentarians berate their predominantly male colleagues who would prefer to keep Godzilla’s existence a secret takes on added resonance when it’s read in this historical context. Public opposition to nuclear-weapons testing found another expression in a “World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs” that took place in Hiroshima in August 1955, and yearly thereafter. Antinuclear activism on a mass scale and Godzilla, in other words, shared the same crib.